Once Upon a Time, There Was Reason

A history of public campaign financing in Nebraska.

By: Jack Gould, CCNE Issues Chair

1985-1992

I joined Nebraska’s Common Cause State Board in1985 in the midst of a major effort to deal with campaign finance reform. Board Chair Bill Avery and board member Ruth Thone had been delegated the responsibility of creating a task force of interested parties to see if anything could be done to keep campaign spending down. It was a major concern that some state legislative campaigns were spending in excess of $100,000.

As a new board member, I was more of an observer than a contributor to the discussion, but I was intrigued with the confidence that both Avery and Thone had that the legislature would actually pass any kind of limits on political campaigns. It was not a surprise that the League of Women voters joined the task force but Avery and Thone had recruited such dignitaries as Speaker of the Legislature Dennis Baack, trucking executive Duane Acklie, and lobbyist Walt Radcliffe. Both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party also were represented.

The task force started the discussion by considering efforts in other states which had turned to contribution limits. Those limits seemed to have some success, but large donors seemed to find ways around contribution limits. The discussion then turned to the possibility of limiting spending. Rather than trying to monitor many thousands of donors, it would be easier to keep track of individual candidates. The problem with spending limits was a constitutional one. Could the state actually limit spending?

Common Cause had always argued in favor of public funding of elections but would the public permit tax dollars to be spent on campaigning? It seemed unlikely that the legislature would support the idea fearing a public backlash.

The final bill known as the Campaign Finance Limitation Act, CFLA, would be sponsored by Speaker Baack. It was the result of many compromises that included key safeguards and incentives. The components of the bill included the following:

- Voluntary Spending Limits – all candidates for state offices would be required to sign an affidavit stating that they would agree to abide or not abide by the state’s campaign spending limit. Non-abiding candidates were also required to provide an estimate of how much they planned to spend on their campaign.

- Public Funding – abiding candidates, when running against a non-abiding candidate, would be given public dollars equal to the difference between the limit and the non-abiding candidates estimate when the non-abiding candidate’s spending actually exceeded the state limit. (the limit became the Trigger)

- Aggregate Contribution Limits – all candidates could only accept contributions from unions, corporations, PACs, and political parties if the aggregate figure equaled half of the spending limit. (The first legislative spending limit was $75,000. The total contributions from the above could only amount to $37,500)

- Public Dollars – the legislature provided a one-time startup of $50,000. There was a voluntary $1 state income tax check-off which generated an average of $7,500 annually. The bulk of the public funding would come from NADC through fines and fees.

It was clear that other than the $50,000 startup money, no tax dollars would be used for public funding. It was also clear that there would not be enough funding to cover all the state campaigns until more dollars were generated.

In 1992, Speaker Baack introduced the CFLA and it passed.

1998 – 2000

By 1998, it appeared there was enough funding that had been generated to only cover legislative campaigns. The majority of this money had been generated from late filing fees.

Most legislative candidates abided by the spending limit. Many candidates who chose not to abide, estimated at the limit knowing that there were opportunities during the campaign cycle where they could increase their estimate.

The CFLA worked. No public dollars were triggered and nearly all candidates spent at or below the spending limit. Candidates seemed to realize that triggering public dollars by exceeding the limit could become a negative campaign issue.

- Primary Election Limit – $ 37,500

- Total Limit (Primary and General) – $75,000

- Aggregate Contribution Limit – $37,500 – was part of the total

By 2000, there was enough funding to cover all state campaigns except the governor’s campaign.

2000

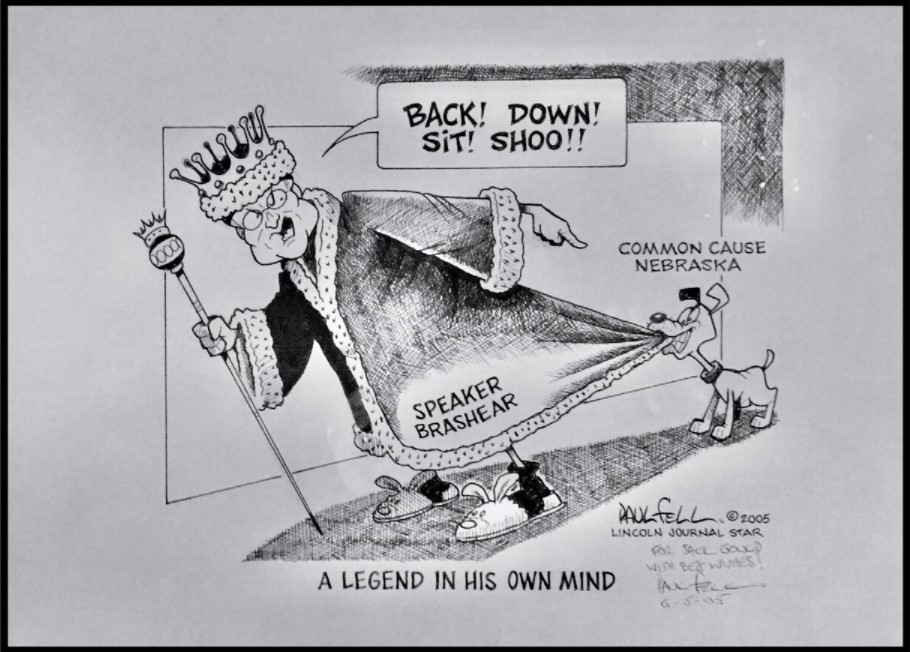

From the time of his election in 1995, Senator Brashear brought legislation to repeal or weaken the CFLA claiming it made Nebraska look like a “backwater state.” In his view it was a violation of the First Amendment.

Common Cause and the League of Women Voters testified against Brashear’s bills and the legislature proved reluctant to oppose something that might open the flood gates to campaign spending.

But in 2000, a new threat appeared. Dr. Randy Ferlic decided to run for the University of Nebraska Board of Regents. No one had ever spent over $50,000 on a regents’ campaign and that was the spending limit established by the CFLA. Rosemary Skrupa was the incumbent regent who agreed to abide by the spending limit. Dr. Ferlic would not abide and estimated that he would spend $350,000 on his campaign. This meant that Regent Skrupa would be entitled to $300,000 as soon as Ferlic’s expenditures exceeded $50,000.

As soon as I saw Ferlic’s estimate, I called his home and asked if this was his actual estimate. He assured me that it was, and he would spend every bit of the money. He also said he wasn’t just running to get the football tickets.

Ferlic waited till the last three weeks of his campaign before exceeding the $50,000 limit and then spent all of $300,000 on advertising. Dr. Ferlic won easily. Regent Skrupa only accepted $27,000, just enough to cover her expenses. It seemed that one of Dr. Ferlic’s goals was to severely weaken the CFLA but Skrupa’s generosity saved the day.

2002

In 2002, incumbent Regent Nancy O’Brien was opposed by Howard Hawks for the University position. Probably having witnessed Skrupa’s defeat, O’Brien refused to abide by the limit. Hawks, however, set the stakes high by estimating at $400,000. O’Brien only spent $106,910. Hawks spent $405,124 and won. Once more the CFLA was saved. Had O’Brien abided by the limit, she would have received $350,000 as soon as Hawks spent over $50,000.

2005

In 2005, David Hergert announced he would run against incumbent Regent Don Blank. Blank agreed to abide by the $50,000 limit. Hergert would not abide and estimated spending

$150,000. Hergert spent $149,000 but failed to file the reports that would have triggered the public funds to Blank. He had done a similar thing in the primary. I had a call from Senator Beutler voicing his concerns about the violations. With Common Cause’s approval, I filed a complaint against Hergert with the Accountability and Disclosure Commission. In a closed hearing, Hergert was fined $33,000. After paying the fine Hergert foolishly went public claiming he paid the fine, so he was entitled to the job.

Both Senator Beutler and Senator Chambers were prepared to go one step further. Jointly they filed a bill to impeach Hergert. After meeting with both senators, I met with Matt Schaefer, president of the UNL Student Senate, urging him to bring the issue before the student representatives at the university. The UNL Student Senate voted unanimously that Hergert should not be a regent.

I then asked Mary Beck if she would bring the same question before UNL’s Faculty Senate. She was reluctant but after meeting with both Senators Beutler and Chambers, she brought the question to a vote. With only 5 dissenting votes, the faculty supported Hergert’s removal.

The Impeachment battle on the floor of the legislature was ugly. At this point in time, Senator Brashear was the Speaker of the Legislature. Brashear represented Hergert as his lawyer at the NADC hearing. He also defended him vigorously on the floor of the legislature during the debate to impeach. When the vote to impeach passed, the margin was slim, a mere one vote.

Republican Senator Schrock cast the deciding vote. When he stood up, he argued that the university students and the UNL faculty did not want a cheater sitting on the Board of Regents. Brashear tried to humiliate Schrock by arguing that he was a disgruntled neighbor of Hergert and was letting his personal feelings interfere with his better judgment. A trial would follow.

The impeachment trial took place before the Nebraska Supreme Court. Hergert had several lawyers, but it was David Domina that represented the Unicameral. Without any notes, Domina gave an impassioned presentation. There had only been one other impeachment trial in Nebraska history and that had been back in the 1800s. The negative student and faculty votes were not legal grounds for the dismissal of Regent Hergert, but they were important points revealed by Domina in the trial. The court ruled against Hergert, and he was removed as a Regent in 2006.

Hergert’s act of deception during the election must have alerted the FBI. In 2009, the Federal Government charged Hergert with 18 counts of bank fraud. It had nothing to do with the CFLA. It was about illegally accepting government payments.

It was difficult to understand why three individuals were willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars for an unpaid position that had a $50,000 dollar spending limit. No one had ever spent over $50,000 and Ferlic was quick to joke that it wasn’t for the football tickets. All three did have three things in common, however. They wanted to put the CFLA funds in jeopardy forcing tax dollars to be spent. They campaigned on ending stem cell research at the University of Nebraska. They all had ties to Speaker Brashear.

Speaker Brashear was the leading advocate at the legislature for ending stem cell research and banning abortions. Brashear vehemently opposed the CFLA and knew how limited the public funds were. He donated to both Ferlic and Hawks campaigns and he was Hergert’s legal counsel during the NADC hearing. He also aggressively defended Hergert during the impeachment debate despite his conflicts of interest.

It seemed to me there had been a plan that could achieve two of Brashear’s goals: 1) put the CFLA out of business and 2) end stem cell research. Fortunately, the University wanted the federal dollars supporting the research and Hergert’s impeachment took much of the vigor out of the battle against the CFLA.

2008 – 2011

In 2008, Senator Beutler tied the spending limits to the cost of living, making the limits more reasonable as the costs of campaigns increased.

Efforts to repeal the CFLA continued being led by Senators Adrian Smith, Philip Erdman, and Scott Lautenbaugh. Common Cause and the League of Women Voters defended the act at every hearing designed to end it.

2012

In 2010, Citizens United and in 2011, Arizona Free Enterprise vs the FEC, brought the CFLA trigger into question. It was argued that triggering public dollars to abiding candidates based on the expenditures of the non-abiding candidate were unfair to the non-abiding candidate. In a political campaign, the trigger could act as a punishment for the non-abiding candidate. Attorney General Bruning was required to bring a case challenging the CFLA. Under Nebraska law, the Secretary of State had to defend the law. Common Cause, with the financial help of Dick Holland, entered the case as third-party interveners. We knew the CFLA was doomed but it was important to show public opposition to the inevitable decision. The CFLA was declared unconstitutional in 2012.

CFLA Success: 1996-2012

- Most candidates either abided by the limit or estimated at the limit.

- By 2012 the legislative spending limit had not exceeded $93,000.

- Public money was only triggered 11 times and was never more than $33,000.

- By 2012 there was more than $1,000,000 in the CFLA fund.

- The aggregate contribution limit worked and remains constitutional, but was lost when the entire CFLA was declared unconstitutional.

2018 Legislative Races: No Limits, No Reason

Overall, 48 candidates spent $6,489,464 running for 24 unicameral seats that pay $12,000/year.

- 14 candidates spent over $100,000

- 5 spent over $200,000

- 3 spent over $300,000

- 3 spent over $400,000

- 25 total candidates exceeded $100,000

- 7 candidates were unopposed but spent over $50,000 each.