The People vs. The Politicians: The Case Against Gerrymandering in the Court of Public Opinion

Americans concerned about the dysfunction of our political system are increasingly rallying around one concrete and surprisingly non-controversial solution. They are working to end gerrymandering, the process by which politicians design convoluted legislative maps in order to protect incumbents, avoid accountability and gain partisan advantage.

Unlike the hot-button political issues that are ripping this country apart, outrage over gerrymandering transcends the partisan divide, pitting voters not against each other but uniting them against self-interested politicians of both parties.

Gerrymandering undermines democracy by letting legislators, who are supposed to be democratically elected, choose their voters instead. Gerrymandered districts are almost never competitive. Candidates feel more beholden to party leaders and their funders than they do to their constituents. And a party can win the majority of votes in a state but end up with only a small minority of the legislative seats — if the opposition controlled the last remapping.

Rally at the Supreme Court as the justices hear Rucho v. Common Cause, a landmark lawsuit against Republican gerrymandering in North Carolina and Lamone v. Benisek, a Democratic Party gerrymander in Maryland., Tuesday, March 26, 2019 in Washington. (Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks)

The Supreme Court is currently deliberating over Rucho v. Common Cause out of North Carolina and another similar case of extreme partisan gerrymandering in Maryland, and its rulings could have dramatic effects on how state politicians draw maps.

Meanwhile, however, grassroots campaigns to end gerrymandering are plowing ahead – most successfully in states where voters can gather signatures to get redistricting reform on the ballot.

“We’re witnessing a civic awakening,” said Karen Hobert Flynn, president of Common Cause. “We’ve taken the ultimate insider issue and turned it into a popular cause that people are protesting in the streets about. Voters are activated, and they want politicians to know their little insider game has to end.”

Trump is undeniably a factor. His election and his approach to governing have left many Americans concerned about the fragility of our democratic system. Some see fighting for fair elections as a way to channel their frustration.

And to the extent that Trump supporters were responding to his campaign against establishment politics, entrenched interests and the need to “drain the swamp,” the fight to end gerrymandering works for them as well.

The movement also benefits from simple and effective messaging. Gerrymandering itself may be complicated to explain, but the notion that voters should be picking their politicians — not the other way around – is an easy sell.

“That is a message that has really resonated,” said Yurij Rudensky, a lawyer who focuses on redistricting issues at the Brennan Center for Justice. “And I think that people viscerally understand the inherent conflict of interest that exists when politicians are able to draw their own districts.”

Talk to grassroots supporters of ending gerrymandering, and you hear that word – resonate – a lot.

“It resonated because I’ve been – as most of us are – very concerned with the dysfunction in our national political system,” said Brian Miller, of Gambier, Ohio, who was attending a rally outside the Supreme Court while attorneys inside argued Rucho v Common Cause and Lamone v Benisek in March. “Gerrymandering is really the heart of it all.”

Grassroots volunteers who go door to door to talk and hand out literature about redistricting report back that the response is overwhelmingly positive. “It appeals to people,” said Keith Oberg, of Arlington, Va., who recently canvassed on behalf of a bill that would put a redistricting initiative on the ballot in his state. Unlike when he canvasses for particular politicians, he said, “nobody yells at me.”

“I’m really very nonpolitical, but it seems like our democratic process is being attacked on a number of fronts,” said campaign volunteer Seth Craig, of Fredericksburg, Va., also rallying against gerrymandering outside the Supreme Court. “This is something that’s kind of fixed in the background, that kind of eliminates people’s choices,” he said. “This is one we can work on today.”

Representatives of the grassroots organizations that won redistricting-reform ballot measures in Michigan, Colorado, Utah, and Missouri spoke earlier this year at a “Terminate Gerrymandering Summit” hosted by former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger at the USC Schwarzenegger Institute for State and Global Policy.

Michigan’s Katie Fahey, who famously launched what became a successful ballot initiative in Michigan with a single Facebook post, described the gerrymandering opponents’ secret weapon.

“Nobody is happy with the state of politics. Nobody!” she said. She and other volunteers with the Voters Not Politicians group often began their conversations with voters by asking: “Are you happy with the state of politics?”

“And, big shocker, nobody is,” Fahey said. Urban, rural, it didn’t make a difference. “Even extremely apathetic voters” respond emotionally.

“Fairness, transparency, wanting a better world, a better state — that is something that a lot of us have in common,” she said. And people recognize that “politicians are not going to give themselves less power,” she said. “So, it’s up to us. It’s up to people … We the people are the only ones who can fix it.”

Catherine Kanter, the campaign manager for Better Boundaries Utah, explained how voters in deep-red Utah ended up backing a citizen commission in November. Volunteers made a conscious effort not to get sucked into discussions about which party stood to gain, but instead focused on “incumbent retention,” she said.

“Those are the things we found that people were really bothered by: This notion that you have conflicted individuals drawing their own maps and considering them ‘their’ districts — not the people’s districts — and this idea that communities were getting sliced and diced for reasons that were benefitting politicians, not individuals.”

Kanter said that’s “an important piece of the Utah story, to understand that redistricting reform can happen even in a place where it looks like it’s unlikely.

“We were people who came together even though we were divided in other ways, came together because we were unified over this simple idea … that politicians have to be accountable to their voters and that they’re not when egregious gerrymandering comes into play.”

Clean Missouri campaign director Sean Soendker Nicholson said his successful campaign began soon after the 2016 election, upon the realization that the same people kept getting elected to the state legislature with no competition.

“We had no idea that anyone else cared or anyone else thought about gerrymandering. We just knew that Jefferson City was messed up,” he said. “There was just no competition and people got reelected over and over again. It was a cesspool …

“So, we were trying to figure out how can we get our state legislature back on track, make it more accountable, back to the people.”

Kent Thiry, a healthcare company CEO who supported the Colorado measure noted how much has changed since he was working on the issue in California, where ballot initiatives passed in 2008 and 2010.

“It’s one thing to have an idea that’s the right idea. It’s another thing for it to be the right time,” he said. During the California campaigns, surveys and focus groups showed voters had never heard of gerrymandering. “The world is so different now,” Thiry said.

Rally at the Supreme Court as the justices hear Rucho v. Common Cause, a landmark lawsuit against Republican gerrymandering in North Carolina and Lamone v. Benisek, a Democratic Party gerrymander in Maryland., Tuesday, March 26, 2019 in Washington. (Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks)

“The fear among our populace is almost palpable,” he said. “The number of partisan Ds on the far left, partisan Rs on the far right — and everything in between — that are worried about our democracy is much higher than I’ve ever experienced it.”

With more people understanding gerrymandering and its significance, he said, “the woods are filled with kindling; it’s just so important that some of us light the match.”

Some observers think gerrymandering is “suddenly” an issue. “What is truly remarkable is, on one hand we’ve come so far, so fast,” said Kathay Feng, national redistricting director for Common Cause. “On the other hand, we’re an overnight sensation 50 years in the making.”

Feng explained: “Common Cause has been wrestling gerrymandering for 40 of our nearly 50 years. It’s really quite simple: regardless of what this or any Court decides, we must replace the self-interest of politicians rigging a system for partisan advantage with the community-interest of impartial, civic-minded people who will draw fair maps.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

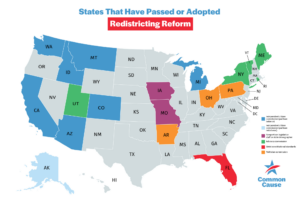

With four states voting to establish citizens redistricting commissions in November 2018 (Colorado, Michigan, Missouri and Utah), that makes 17 states in all that have adopted some checks and balances to limit gerrymandering.

So, what states are next?

Virginia

Advocates of redistricting reform in Virginia won a huge victory in February when the state legislature passed the “first read” of a constitutional amendment that would establish a redistricting commission made up of eight legislators and eight citizens. The citizens, including the chairperson, would be selected by retired judges from lists provided by both parties in both chambers of the General Assembly. The final maps would require a three-fourths vote of the legislators and the citizens, and every step of the proceedings would be open to the public.

It is, as Brian Cannon, executive director of redistricting group OneVirginia2021 described it, “the most comprehensive redistricting reform ever passed through a state legislature.”

A poll in December found that Virginians support an independent commission to draw voting lines by a staggering 78 to 17 margin.

But the battle isn’t over. Another major grassroots mobilization will begin after state elections in November 2019, because the new legislature has to pass the resolution a second time for the amendment to make it to the ballot.

Arkansas

Entrenched interests have often fought ballot initiatives they didn’t like by launching their own initiatives to confuse or divide voters. In Arkansas, two groups are pushing for ballot measures in 2020 to establish redistricting commissions – but only one of them is acting in good faith. The first proposal would follow the bipartisan model adopted in other states: an independent commission with bipartisan and unaffiliated members. The other is a nakedly partisan plan to preserve Republican control by creating a commission with a majority of members appointed by Republican legislative leaders.

Oregon

In Oregon, grassroots groups, including Common Cause Oregon and League of Women Voters of Oregon, will likely push to get at least one measure on the 2020 ballot calling for an independent redistricting commission. In that state’s legislature, it’s Republicans who are pushing for change, while the Democratic majority is putting up resistance.

And Beyond

Four other states – Illinois, Mississippi, Nebraska and Oklahoma – could have anti-gerrymandering measures on the 2020 ballot.

Grassroots coalitions are actively promoting legislation in several other states, including Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

And there’s some movement in Congress — although Republican senators have vowed to block it. House Democrats passed an omnibus democracy-reform “For the People Act”, in March, designated House Resolution 1 (H. R. 1).

Among its many provisions, H.R.1 requires every state to set up a 15-member non-partisan citizens commission charged with remapping congressional districts after each decennial census. The selection process, mapping guidelines and voting rules all require a nonpartisan approach.

The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Rucho v. Common Cause is expected in June. One result is inevitable, regardless of how the justices rule, Hobert Flynn said. “It will be a rallying cry for people taking on politicians.”