Introduction

Politics costs money. Runaway campaign spending blocks better government policies because can didates turn to the wealthy and industry for support. The support comes with strings because big spenders are investing in policy outcomes.

Citizen-funded election programs step in to create space for policies that favor large swaths of every day Americans. Particularly when combined with restrictions on lobbyist and government contractor contributions, these reforms represent the best way to prevent government capture by the wealthy.

Some claim that these programs are too fragile a “fix” in a system that allows the wealthy to spend massive sums. Others ask whether it really leads to “better” government, which can be hard to prove.

We talked to legislators, candidates, lobbyists, regulators, academics and Connecticut voters. In short, we found that the experiment in Connecticut is working, and the state has become a national model.

Ordinary citizens are more empowered to participate in democracy and better represented by those elected to office. Races are much more competitive, and the legislature is more representative of the state; local small donors matter. The Citizens’ Election Program (CEP) has been embraced by candidates, and many claim that high participation by elected legislators has led to better policy outcomes.

One bill alone, the “bottle bill,” which passed a decade ago, led to both a better policy outcome and savings for the state that has more than paid for the entire program.

Citizen-funded elections may not be a panacea for all issues, but it is the best instrument we have to combat the problem of money in politics. All instruments need to be tuned over time. Amendments are needed so that reform programs continue to fulfill their ultimate goals.

We need to support the agency charged with administering this historic reform by giving it the resources it needs to deliver the full promise of small-dollar donor democracy. And we need to help everyday Americans better recognize the impact of these reforms on their daily lives.

The nation is watching.

We are facing extraordinary challenges, including foreign interference in our elections, a president impeached by the House of Representatives and an attack on foundational states’ rights by a president who claims “absolute authority” over our state leaders’ day-to-day actions to protect us in the face of a global health crisis.

This is a time to protect and lift up the inspiring model of Connecticut’s Citizen Election Program. It has set the standard for a state model of reform that inspires hope for change across a country ready for healthy democracy reform. The future of our democracy may depend on it.

BETH A. ROTMAN

Director of Money in Politics and Ethics

Common Cause Education Fund

Participation in the Program and Staying Power

In its inaugural year, the Citizens’ Election Program exceeded every expectation for participation in the first run of a landmark program in 2008.

That year, an astonishing 73% of candidates running for the General Assembly participated in the voluntary program, surpassing the first-year participation rates of Maine and Arizona, the only other states with similar programs.1

Even more important is the fact that candidates—both incumbents and challengers—have continued to join the voluntary program in record numbers. This is not something to be taken for granted.

During the first decade of the program’s operation, from 2008 to 2018, an average of 76% of all legislative candidates joined the CEP.2 In 2018, a staggering 85% of General Assembly candidates joined the CEP, which represents an all-time record.3

Not surprisingly, this sustained high participation makes a difference in the program’s impact, from encouraging more people to run for office to impacting the focus of people elected to serve in state government.

Small Donors Fund Legislative Candidates, Replacing Political Action Committees (PACs), Lobbyists and Contractors

The types and sources of campaign contributions changed markedly in Connecticut legislative races because of the high rate of participation in the CEP.

In 2018, an extraordinary 99% of the campaign funds used by legislative candidates came from individuals.7

This stands in sharp contrast to preprogram practices when less than half of the contributions made to political candidates came from individuals. For example, in 2006, nearly half of the $9.3 million raised by candidates came from lobbyists, PACS and other entities.General Assembly Contribution BreakdownState of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”[/efn_note]State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”

The creation of the CEP fundamentally changed the landscape of campaign fundraising. In addition to providing a new source of funding for candidates participating in the CEP, Connecticut’s good government reforms turned off the spigot of campaign contributions from principals of state contractors and reduced lobbyist contributions to $100. The statute also prohibited lobbyists and principals of state contractors from soliciting on behalf of candidates, known as “bundling,” where one could collect contributions from others as a way to deliver large sums to candidates.

As an added measure to reduce the influence of special interests, candidates participating in the CEP were also barred from accepting contributions from political committees and other entities. The new funding sources, together with the restrictions on special interest money, resulted in a very different political landscape.

General Assembly Contribution Breakdown8

In the 2018 legislative elections, 99% of campaign funds came from individuals.11 The bulk of the funds served as qualifying contributions for candidates participating in the CEP. The CEP requires candidates to raise small contributions from residents of the candidate’s district, making small-donor funds from Connecticut residents very valuable. The CEP’s reliance on these small-donor funds transferred political power from wealthy contributors and businesses back to the people.

Candidates generally agree that the CEP—and the strings-free money it offers to candidates—has reduced even the appearance that elected officials are beholden to lobbyists and special interest groups. The aptly named program truly serves the citizens of the state of Connecticut.

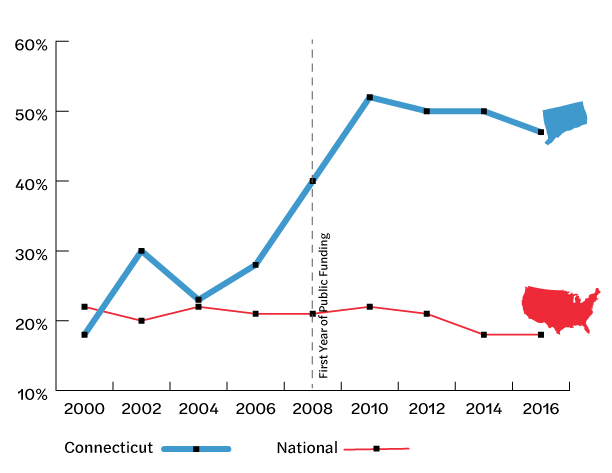

Contributions from Special Interest Donors to Winning Connecticut Legislative Candidates From 2000 to 2016

The Campaign Finance Institute isolated contributions from organizations that represent private groups as one determinant of special interest influence. The average total funds from special interests (defined as organizations representing private groups) to winning state candidates in Connecticut dropped 98% after implementation of the CEP.13

“Corrupticut”—Influence for Sale

With the resignation of Governor John Rowland in June of 2004, one of the worst episodes in Connecticut’s political history closed.

For a former boy wonder of politics, Rowland’s demise came quickly. In 2002—the same year voters elected Rowland to a third term—federal investigators began to look into political corruption in his administration. Two years later, Rowland resigned from office amid allegations of bribery, contract steering and tax evasion by state officials and private contractors, including charges that the governor and his including charges that the governor and his family had accepted lavish gifts from contractors.

Coming on the heels of other scandals involving politicians from both major parties—corruption in the Bridgeport and Waterbury mayors’ offices, kickbacks from investment firms for the state treasurer and bribery of a state senator—the Rowland scandal cemented the state’s reputation for political malfeasance with the nickname “Corrupticut.”

While bribery and kickbacks were already legal violations, there were loud calls to address the ties between wealth and policy outcomes. These ties often begin on the campaign trail and continue even when many have good intentions. The need for perpetual fundraising can make this seem unavoidable.

One prominent lobbyist described lobbying the General Assembly years ago:

I realized this was how the game was played. We met off-campus and we were told to bring a list of our clients. We went down the client list together and discussed how much money each client was good for. Some lobbyists felt it was a shakedown and wanted a shower afterwards. I walked out with a sense of relief because then I understood the expectations of me and my firm, and I could help my clients. And now I knew that I was able to raise money in the $20,000 range. But, to use a mafia term, if we were “light,” we could likely expect to hear from people.

Also, if we gave the impression that our firm had a huge PAC and we were ready to write checks, we could really get stuff done.

At the end of the session, we would be asked what we needed. I knew I could ask for five or six bills that they would try to get in the budget implementer. It wasn’t the biggest stuff, like Medicaid for hospitals, but smaller things like nickel deposits on bottles were possible because we had greased the wheels. (Prominent lobbyist, personal communication, January 16, 2020)

This account of a “client list” meeting practice was confirmed by others. And even if most politicians never engaged in actual influence peddling, in the wake of the political scandals, the public perceived that influence at the capitol was for sale.

An Engaged Public Demands Reform

Seizing upon the public’s demands for significant reforms to clean up Connecticut politics, the state’s new Republican governor, Mary Jodi Rell, called for the enactment of campaign finance reform just one month after taking office.

Common Cause played a leading role, working tirelessly and organizing to seize a key moment and opportunity for democracy reform in Connecticut. Under Karen Hobert Flynn’s leadership as state chair and Andy Sauer’s leadership as state director, Common Cause Connecticut, together with the Connecticut Citizen Action Group (headed by Tom Swan) co-led a broad coalition of grassroots and issue groups in the push for sweeping reform.

Known as the Clean Up Connecticut Coalition, members went beyond the traditional democracy reform organizations, known as “good government” groups, to include others who understood that these reforms were essential to strengthen the integrity of Connecticut’s democracy, from labor unions to religious organizations and groups primarily focused on civil rights, social welfare or the environment. The coalition waged an extremely effective paid and earned media campaign, coupled with a strong grassroots effort and diligent good government lobbying that kept pressure on the governor and legislative leaders over time.

Common Cause’s overarching goal was to return power to the people, where it belonged. Common Cause also commissioned Zogby International to survey the public at this critical moment in Connecticut’s history. Eighty-eight percent of the state’s voters (across party lines) who were surveyed “believe that Governor Rell must work with legislators to enact a campaign fi nance reform bill so that future scandals like those of Governor Rowland’s administration might be prevented.” Seventy-five percent of the voters surveyed said, “They are less likely to vote for a candidate who failed to support clean elections.”15

Agreement on a reform package would not come easily, and advocates, organizers, reporters and people across the state had to remain vigilant on the road to reform. Meanwhile, working with national groups and allies brought significant extra resources that made a difference in the fight.

Here are a few snapshots of the activism, engagement and breadth of the reform coalition, fueled by everyday Americans who pushed back against government corruption and demanded change.

Among the thousands of grassroots activities led by the coalition—demonstrations, targeted mailings, phone banks, letter-writing campaigns, door knocking, and letters to the editor—activists held Clean Cars for Clean Elections Car Washes in targeted towns. Several state and local elected officials participated in the car washes, together with Karen Hobert Flynn and activists Jack, Peter, Danny and Michael Flynn.

After reports that Governor Rowland had accepted a hot tub from state contractors, advocates placed a hot tub outside the state capital. Here, Sister Mary Alice Synkewecz and Sister Suzanne Bryzinski of the Collaborative Center for Justice are pictured in a hot tub similar to the one that Governor Rowland had accepted as one of many lavish illegal gifts. Advocates were also known to drive around the state pulling this hot tub to further engage the public and keep pressure on state leaders to enact meaningful reform.

Advocates launched an armada of boats filled with chanting protesters to follow Senate Republican Leader Lou DeLuca and the lobbyists he was entertaining down the Connecticut river. Press reports described the senator’s reaction as apoplectic. Advocates’ penchant for theater and public confrontation was not lost on potentially wavering legislators.

Advocates Keep Up the Heat on Leaders

There was a lot of pressure to do something big, but legislative leaders struggled to agree on a proposal. So, after the General Assembly could not agree on a proposal in the 2005 legislative session, Governor Rell and Speaker of the House Jim Amman put together a working group to iron out differences between the House and Senate campaign finance bills. After the working group issued its report, Common Cause and its allies pressured Governor Rell to call the legislature into a special session.

The dynamic of Governor Rell and the Democrats trying to out-reform each other was crucial, says Karen Hobert Flynn, president of Common Cause. They would keep egging each other on with public statements, quite confident that the other would not call their bluff. In the end, this brinkmanship helped advocates push them over the cliff to accept the necessity and reality of sweeping campaign finance reform. (Karen Hobert Flynn, personal communication, January 28, 2020)

Advocates and reformers kept the heat on Connecticut leaders to enact sweeping reform. Former senator Don DeFronzo, one of the Senate leaders of the reform, explained,

You cannot overemphasize the role of the good government groups like Common Cause and the public engagement they brought to the push for reform. As the process continued, their influence really grew because they offered such credible information and support. Karen in particular was always ready with good resources, and we relied on this support heavily as we crafted the possible reforms. (Don DeFronzo, personal communication, January 17, 2020)

Legislative leaders crafted a comprehensive bill that ultimately garnered majority support in the House and Senate. On December 7, 2005, Governor Rell signed the sweeping legislation that banned contributions from lobbyists and state contractors and created the CEP, a program that provides grants to eligible candidates who agree to accept only small contributions from individuals and abide by expenditure limits.

The program created an atmosphere in which the most important contributors for a candidate are the individuals living in the candidate’s district. The people restored self-governing by defeating Big Money special interests in one of the great political David and Goliath stories of all time.

Academic studies of the effect of small donors on the political process indicate that state efforts in fostering contributions from small donors tend to encourage less affluent donors to give to a political candidate, thereby increasing lower-income individuals’ participation in the electoral process.17

Launching a Program That Changed the Landscape

Launching a program that changed the entire political landscape would not be easy.

Sen. DeFronzo explained,

The legislation was so broad and complex, and it impacted the system so dramatically. It was so challenging to pass, and it was understood that it would be extremely challenging to implement so many sweeping changes all at once (DeFronzo 2020)

To build and lead the new program, the state elections agency hired Beth Rotman (author of this report), who was then the deputy general counsel for New York City’s nationally recognized public financing program overseen by the New York City Campaign Finance Board. Rotman took the lead in the Connecticut program in late 2007 and began planning for the first election cycle of the new program in 2008.

Rotman wrote program guidelines in every spare moment while lobbying for additional funds to build a strong administrative team. Strong relationships with advocates, reformers, elected leaders and the press would prove invaluable.

At the first public hearing after the first election cycle for the CEP in 2008, academic and political strategist Jon Pelto stated,

I want to congratulate you on an extraordinary job putting this together, from the services provided to individual candidates to the actual process of the Commission. It was an amazing job. Many of us thought it wasn’t possible. You proved us wrong and deserve tremendous credit for putting this system in place. I believe it will go down 10, 15, 20 years from now, when they look back, as the single most important development in Connecticut politics.19

More than a decade later, Pelto’s prediction, as bold as it was then, looks true today. The CEP stands as a model in the very best tradition of the laboratory of the states. It offers a path forward for voters who have had enough of Big Money, and proves it is possible to push back against the outsized influence of wealthy special interests and strike a blow against the era of Citizens United.

The Public Wins Against Big Money

One bill, known in Connecticut as the “bottle bill,” became a case study in how lobbyists and the wealthy special interests they represented could control government policy and cost the public millions of dollars.

For many years, powerful lobbyists for beer and soda distributors ensured that their wealthy industry clients could keep the bottle deposits consumers waive when they do not return cans and bottles to stores. This added up to $24 million a year.

For many years, every attempt to return this $24 million to the state’s general fund—instead of allowing private bottlers supported by lobbyists to keep that unclaimed money—faced defeat. The lame-duck General Assembly in November of 2007 had to vote on a budget deficit mitigation bill and included a measure to reclaim bottle deposits. It lost resoundingly.

Savings From One Bill When People Drive the Government

A few months later, the newly elected members of the legislature, with three-quarters having run un der the new CEP, voted to return the unclaimed bottle deposits to the general fund, giving up to $24 million per year back to the public. Now, after 10 years of program operation, the amount returned to the public totals approximately $240 million.21

This “bottle bill” vote struck many veteran lawmakers, reformers, activists, reporters and members of the public as remarkable. Many still cite this vote as the singularly most powerful evidence that public financing can lead to better governance.

Rep. Chris Caruso wrote about the influence of citizen-funded elections on the General Assembly’s consideration of expanding the bottle deposit:

Some people think it’s impossible to blunt the influence of lobbyists and big donors, but that’s exactly what happened here in Connecticut this year. For many years, environmentalists have tried to expand the bottle bill recycling program, to include 5-cent deposits on plastic water bottles, but the powerful beverage industry and its paid lobbyists were able to stop every effort at reform because they gave thousands of dollars to legislators.

This year, the legislature—with three-quarters of members having participated in the Citizens’ Election Program—voted to expand the bottle bill. We also voted to reclaim millions of dollars’ worth of unclaimed bottle deposits, which takes approximately $25 million a year out of the pockets of the beverage industry and puts that money into the general fund where it belongs. This alone recoups more money than the Citizens’ Election Program costs. This is just the beginning.22

Another long-serving member of the General Assembly commented on the bottle bill, noting a prominent lobbying firm’s experience:

Watching [prominent lobbyists] be ignored on the bottle bill extension for the first time proved that getting the special interest money out of campaigns got special interest influence out of bills. Wow! Voting on the merits.

Opponents of citizen-funded election programs like to call them “welfare for politicians” and talk about them as wasting tax dollars. The Connecticut experience proves that these people-powered programs can pay for themselves while elevating the needs of the public.

Restoring Competitiveness in Legislative Races

Competitive elections keep elected officials more responsive to voters because they give voters a choice.

The CEP has markedly increased political competition in Connecticut, according to detailed reports by the National Institute of Money in State Politics.

In 2004, before the reforms were passed, the lobbyists and wealthy special interests tilted the scales toward incumbents and used money to influence newcomers. Connecticut was ranked in the middle of the pack in standings of competitiveness in the 50 states. In the very first election cycle of the CEP, the state jumped to eighth place and ever since has been consistently one of the two or three states with the most monetarily competitive legislative races in the nation.25

In 2018, Connecticut was ranked first in the nation in legislative elections using the National Institute of Money in Politics standard for monetary competitiveness.27 Because a majority of candidates join the CEP, legislative candidates have access to ample funds to wage truly competitive races, and voters have a real choice at the ballot box

Empowering New Voices Who Have Shaken Up “Politics as Usual”

By reducing the barriers to running for office that Big Money represents, more people with different life experiences and from more diverse backgrounds, women and people of color, saw an opportunity.

Starting with the first run of the Citizens’ Election Program, Connecticut took huge steps toward a more representative and reflective democracy.

Tom Swan, executive director of the Connecticut Citizens Action Group and co-leader of the coalition of activists who pushed for sweeping reform explains,

This system has opened up the door. It’s created an opportunity for a more diverse set of candidates to participate in the electoral process. It has allowed individuals from limited means to compete in a meaningful way while bringing new donors into the process because small contributions actually make a big difference.29

A “Do-Gooder Who Wanted to Make a Difference”

Sen. Mae Flexer, who became a state representative with the first run of the CEP and now heads the Government Administration and Elections Committee, explained,

I ran because there were not a lot of young women in the legislature. I was not connected to wealthy people or lobbyists, so the Citizens’ Election Program made my run possible. I was a do-gooder who wanted to make a difference, and I think I have been able to do that as a legislator. I also encourage other women to run for office in Connecticut because women work differently and make great leaders. (Sen. Mae Flexer, personal communication, January 17, 2020)

Women make up 51% of the population of Connecticut but are under-represented in the legislature, as is true across the country. But the 2008 General Assembly races led to a great year for electing women to serve as legislators. Some of these women are still serving today and have assumed significant leadership roles while mentoring new female candidates.

Before the launch of the program in 2007, there were 53 female members of the General Assembly out of 187 seats, holding just 28% of the seats. This jumped to 59 female members in 2008, with 51 women in the House and eight in the Senate. This 2008 number was the peak for female legislators until the last General Assembly election in 2018 when 63 women were elected to serve—52 in the House and 11 in the Senate—showing steady gains during the decade of citizen-funded elections, up to 33% of the legislature and climbing.31

“Upending the Playing Field”

Sen. Gary Winfield has been an outspoken supporter of citizen-funded elections from the beginning, explaining,

Without public financing, I would not have been a viable candidate. Without the grant funds provided by the Citizens’ Election Program, the ability to mount a sustainable campaign would have been almost impossible. I am a candidate of color and I did not come from money. I was not the candidate picked by a political party or machine apparatus. The Citizens’ Election Program made it possible for me to run and serve the public—as one of them.33

Winfield was able to win his state representative seat in the first run of the program. He is still a member of the General Assembly, now as a state senator. “It not only leveled the playing field; it completely upended the playing field.”34

From Opponent to Supporter: The Nonpartisan Nature of Small-Dollar Donor Programs

Former senator and Republican minority leader John McKinney did not vote for the original bill. But he admitted that he missed a key goal of the program in those early days of developing the bill that would become the CEP: the increased opportunity for candidates to compete.

“What I missed at the time [passage of the bill] was not the ‘clean elections’ from the ethics standpoint but was the ability to attract more people to run for office,”37 he said. McKinney disclosed that it was not until he had to travel the state recruiting people to run against incumbents that he realized the impact of the program.

When I can walk into a room and sit down with a person, not tell them the full truth about how much time they are going to miss from their family and their jobs but say listen here’s what you have to do to qualify and you’ll get the exact same amount of money as the democrat incumbent. That made it a lot easier to get people to run for public office.

McKinney continued, “I think that may be the greatest contribution of this bill. That it opens it up for anyone to run for public office.”

He stressed how important competitive races are to our democracy. The program “enables you to run candidates in districts even where the registration numbers are overwhelmingly in favor of one party or the other and get that message out.”

Former representative and Republican minority leader Larry Cafero echoed the sentiments of his counterpart in the Senate—the program provided a new opportunity for Republicans to compete against incumbent Democrats.

Cafero gave credit to the program for the increased number of Republicans in the House. He pointed out that the election of Republican governors never translated to the legislative chambers. Cafero stated that he was in the minority during his entire 22-year career. In 2007, before the program, his caucus had 44 members. By 2017, the number shot up to 72. Cafero explained,

The irony of it is, this very bill probably was very much responsible for us getting there. That changed the whole game. All of a sudden, we were on an equal playing field.

Cafero pointed out that before the program, a Republican who might have wanted to run in New Haven or Hartford or Bridgeport “couldn’t catch a cold. They couldn’t raise five cents.”

With the contribution limits and grant from the public financing program, that candidate now has an equal amount of money as the incumbent in that town. “They have a shot. They have a shot more now than they ever did before.

“Is it going to be easy given the demographics? Never,” Cafero pointed out. “But a heck of a lot easier and more of a chance than [they] had in 2006 or 2004.” 38

Minor Party Success: Enough to Get My Message Out

Other minor party candidates have successfully won grants over the past decade, and now the Green Party has also seen a candidate’s opportunity boosted by the program. Green Party candidate Mirna Martinez was the recipient of the first Green Party grant from the CEP in the February 2019 special election for the 39th State Representative District. Democrat Anthony L. Nolan won the four-way race with 51%, with Martinez, the runner-up, at 29%.

As a three-term board of education member, Martinez had familiarity with the community she hoped to represent. She credits the program for her ability to mount such a strong campaign.

The quality of my run was greatly enhanced by the public financing grant, she said. I was able to get the message out, hire campaign staff and overall run a more effective campaign. (Mirna Martinez, personal communication, January 16, 2020)

With so much Big Money exaggerating the speech of a few, it is hard for some people to be heard. Connecticut proves that by providing enough funds for candidates to be heard, voters are able to cast ballots based on a range of perspectives and ideas to set the course for their communities and the state moving forward.

Small-Dollar Contributions: “Elevating the Peoples’ Voice”

Rep. Quentin “Q” Phipps served as planning and zoning commissioner and then treasurer in his home town, but when his state representative’s seat was open for the first time in 10 years, he set his sights on higher office. Phipps used the CEP in his win to become Middletown’s first black state representative.

Phipps agreed that the program opens the door for more people to run and is “unquestionably an equalizer in the process” (Quentin Phipps, personal communication, January 16, 2020).

Not only does the program provide a means for more people to run for office, but the lack of reliance on “dialing for dollars” and the constant ask for funds allows candidates to spend more time meeting with constituents and engaging them in the electoral process.

By not having to concentrate on fundraising, Phipps said, I was able to spend more time meeting with the community, discussing issues that matter, and elevating the peoples’ voice. (Phipps 2020)

Engagement With Members of the Community

Rep. Joshua Hall was first elected using the CEP as a Working Families Party candidate in a 2017 special election. He went on to use the program in his successful reelection bid in 2018.

Mounting a successful special election campaign is difficult because of the compressed time frame of the election cycle: 46 days. Running in a special election without the party nomination is even harder. Hall explained,

I realized I was running uphill with a boulder on my back. I would not have been able to muster the type of support I needed to be successful without the Program. (Joshua Hall, personal communication, January 17, 2020)

Hall credited the program grant for affording him a much broader and effective reach.

Instead of relying on money from special interests, who may not have our constituents’ best interests in mind, the Citizens’ Election Program provides the opportunity for endless engagement with members of the community you represent. (Hall 2020)

One way the candidates involve their community is through soliciting small-dollar contributions from within the candidate’s district. Hall explained that the low threshold of support ($5) allowed folks of every means to participate in the process.

Without question, I was able to engage individuals who had never participated in elections before. They now were able to play a significant role.” (Hall 2020)

“We’re in No One’s Pocket. We Are Not Bought.”

Rep. Anne Hughes, a licensed master social worker, was a first-time candidate in the 2018 cycle. She successfully flipped her district from Republican to Democrat for the first time in 34 years.

Hughes stated that the program provided her with the means to run a successful campaign,

For someone like me, a working individual who is not wealthy, the Program was absolutely critical in giving me an opportunity to participate.” (Anne Hughes, personal communication, January 16, 2020)

Hughes also noted that the program fundraising requirements provided a vehicle to engage constituents who never participated in the process. Students, young people and first-time voters were all able to make small-dollar contributions and be involved in the process of her qualifying for a grant. Hughes explained,

Beholden to ALL of the People

Tara Cook-Littman is a mom and a public interest attorney who has worked as an advocate for a variety of social and economic issues, including genetically modified organism (GMO) labeling. She was part of a successful effort to push the General Assembly to pass the nation’s first GMO labeling bill, and she credited the CEP for her successful advocacy, explaining,

I was up against the food industry, the chemical industry—the most powerful interests in the country. Many other states without the contribution restrictions that Connecticut has, wouldn’t even dream of trying to pass a GMO labeling bill.

The only chance we have at passage is because of the Citizens’ Election Program. The legislature is not beholden to the lobbyists of big industries. They are beholden to the people of the state of Connecticut.(Tara Cook-Littman, January 16, 2020)

After seeing how the program made her GMO labeling advocacy work more successful, Cook-Littman even decided to run for office. Although her bid to join the General Assembly was unsuccessful, she has not ruled out another run.

The Program makes running for office accessible to everyday citizens, especially to women and minorities. Beyond opening up the process of seeking office, the Citizens’ Election Program changes the way issues are debated and makes it possible to pass bills that are much better for everyday citizens. (Tara Cook-Littman, January 16, 2020)

Building on her successful advocacy to pass the GMO labeling bill, Cook-Littman is now advocating for a pesticide ban.

New Faces in the Chamber: Real People Making a Real Difference

Rep. Jillian Gilchrest teaches social welfare policy and psychology of women at the University of Saint Joseph. She beat a 23-year incumbent in the Democratic primary and went on to win the general election.

Gilchrest said the program played a major role in her decision to run because money was a “non-issue” (Jillian Gilchrest, personal communication, January 17, 2020).

Going against a 23-year incumbent, who was held to the same contribution limits, made a difference. (Jillian Gilchrest, January 17, 2020)

Gilchrest was able to reach the qualifying thresholds in only 11 days of fundraising. This gave her more time to focus on the issues. She recalled that constituents were shocked that she wasn’t asking them for more money.

Reallocating Power and Changing the Debate

The success of the CEP has been held up as a model and has pushed others to move reform.

Former senator Don DeFronzo shared the following:

I could never have imagined that it would work out so well. I couldn’t have predicted this level of extraordinary success, or that the program would be so widely used. It has had a remarkable impact on the quality of the debate. The reforms went beyond trans forming elections—they changed the way state government operates. (DeFronzo 2020)

Solving the systemic problems facing our democracy requires reallocating power. By reigning in the power of Big Money, the CEP has started a sea change in how people engage democracy. Opening up state democracy to new voices has also impacted the focus of many legislative debates on issues that matter to ordinary citizens. Elected leaders and lobbyists confirm, one after the other, that the new debate has encouraged new policies that favor everyday Americans over Big Money, from healthier food choices in schools to guaranteed paid sick days and sweeping consumer protections in industries that were once major campaign contributors.

To highlight one key example, Connecticut became the first state in the nation to pass sweeping health care across the state for service workers after the CEP changed the landscape. Previously, opposition from business interests had blocked any progress on paid sick leave. In 2010, however, the first gubernatorial candidate to run and win under the CEP campaigned on a promise of paid sick days. One year later, he supported paid sick leave once elected, together with the General Assembly made up of a majority of legislators running and winning while participating in the small-dollar democracy program.

The state’s paid sick day law is ultimately a testament to what happens when the debate shifts, and wealthy interests lose their stranglehold over policy discussions. Freed from reliance on large checks from the state’s lobbyists and chamber of commerce, state elected leaders were able to focus on the needs of more voters, starting on the campaign trail and continuing in office. This has meant paid sick leave coverage for large swaths of everyday Americans, including many of the health-care workers heroically serving in the current pandemic.

The People Must Win and Win Again

Change can be hard. The implementation of such sweeping reforms was not simple. And preserving clean elections coupled with the necessary oversight of public money is still not a given to all state leaders. Shortsighted and self-interested legislators, and the Big Money interests behind them, have stripped away at the program’s funding time and time again, claiming the need for fiscal discipline. They have also attacked the agency charged with over seeing the program, stripping it of many needed resources.

While the state has seen difficult financial times, we cannot put a price on clean government. Connecticut has started to change the culture of democracy, but these attacks make clear that the fight is not over. Advocates and the people of Connecticut cannot count this as a win and lose their vigilance. As with many big reforms, the people have to win and win again.

Common Cause President and Connecticut resident, Karen Hobert Flynn, explains,

It is amazing to compare where we are now in Connecticut to where we were not so many years ago. As I travel the country and meet with candidates and lawmakers from around the United States, it is stunning to see the difference between the Connecticut legislature and other states. I was proud to highlight Connecticut’s progress when I testified before Congress in support of Congressman John Sarbanes’s transformative For the People Act (HR 1), which passed the House of Representatives and is supported by all Senate Democrats.

We stand as a model for others, but Connecticut’s leadership must remain willing to make the hard choices necessary to preserve clean elections. The last thing state lawmakers should do Is take us back to the bad old days when our state earned the nickname of “Corrupticut” (Flynn 2020).

National Impact as the Connecticut Reforms Influence a Movement

When the Connecticut reforms were passed, the state joined only a handful of states and cities in leading the way on small-dollar donor programs. As hopeful legislative candidates started flocking to the fledgling program, Peter Applebome of the New York Times wrote in 2008,

The big story about public financing of campaigns nationally has been Barack Obama’s decision to opt out of the national system. But what’s unfolding in Connecticut may end up being far more influential.41

This was prophetic indeed. With very high program participation by candidates, the CEP achieved key goals and led the way for national and local reform in many other places. Every small-dollar donor program passed over the past decade, and there have been many, owes some debt to the success of the Connecticut program.

The state has become a national model, proving it is possible to strike a blow against the era of Citizens’ United. Ordinary citizens are more empowered to participate in democracy and better represented by those elected to office. The legislature is more representative of the people. Opening up democracy to new voices has had a meaningful impact on issues that matter to ordinary citizens. This is what democracy should be, and it is setting a new standard of reform that inspires others to make change across the country.

Many everyday Americans are unaware of the link between these reforms and their day-to-day lives; there is a price we all pay within our family budgets when wealthy special interests fund the campaigns, political parties, and set the agenda with lobbying. This needs to change, both in order to protect the reforms that have passed and to educate more of the public across the country about the need to pass these reforms in their own communities. We must lift up the inspiring model of citizens’ reclaiming their government from wealthy special interests. To deliver fully on this promise of small-dollar donor democracy and enable everyday Americans to understand the link between their day-to-day lives and their financing of elections, education is critical. This education protects the existing reforms and will help with the passage of the program in new cities and states.

We are at a time in this nation when many Americans are engaged and demanding change. So, we are already on the journey to strengthening our democracy. There is a spirit of hopefulness even in this extraordinarily challenging time, but many need to understand how we can “fix” our money-in-politics addiction in America. Common Cause is working on this while offering hope for our democracy at this critical inflection point for our nation.

Citizen-funded elections lead to healthier democracies and offer a guide to all citizens who believe that democracy is out of balance. Common Cause has been leading the nonpartisan charge for healthier democracy for 50 years, working at the national level and on the ground, state by state. We demand a democracy that works for all of us, but we can only do this together. Join us.

Acknowledgments

The Common Cause Education Fund is the research and public education affiliate of Common Cause, founded in 1970 by John Gardner. Common Cause is a nonpartisan, grassroots organization dedicated to upholding the core values of American democracy. We work to create open, honest and accountable government that serves the public interest; promote equal rights, opportunity and representation for all; and empower all people to make their voices heard in the political process.

The Change Happens Foundation grant made it possible to conduct a first of its kind “deep-dive” evaluation of a statewide public financing reform program (also known as citizen-funded elections) after a decade of implementation. The results of the research are remarkable and simply would not have been possible without our partnership with Mike Troxel and the board members of the Change Happens Foundation. By championing innovative democracy reforms, such as citizen-funded elections and pushing back against the exaggerated role of special interests, the Change Happens Foundation leads the charge to strengthen our democracy.

The nimble leadership of Karen Hobert Flynn, president of Common Cause, former chair of Connecticut Common Cause and a lead architect of sweeping campaign finance reform in Connecticut, makes it possible to work on the structural money-in-politics reforms essential to strengthening the peoples’ voices in our government.

The National Institute on Money in Politics served as a critical resource for our study of money-in-politics reforms. The high-quality analyses of data trends and highlights by the field’s leading scholars and researchers, including Ed Bender, Michael J. Malbin and Pete Quist, make it possible for everyday Americans to actually follow the money at OpenSecrets.org.

Connecticut Government Administration and Elections Committee co-chairs Sen. Mae Flexer and Rep. Daniel Fox held an extremely helpful public hearing on January 30, 2020, featuring and informing our research about the Citizens’ Election Program’s effect on participatory democracy after 10 years of implementation.

The authors also wish to thank Bob Stern of the Center for Governmental Studies; Amy Loprest of the New York City Campaign Finance Board; Scott Swenson, Paul S. Ryan and Cheri Quickmire of the Common Cause Education Fund for their invaluable advice and encouragement on this report; Melissa Brown Levine for copyediting; and Kerstin Diehn for her design.

- “Participation Rates (2006–2018),” State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, https:// seec.ct.gov/Portal/eCRIS/eCrisSearch.

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Participation Rates (2006–2018).”

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Participation Rates (2006–2018).”

- “Participation Rates (2006–2018),” State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, https:// seec.ct.gov/Portal/eCRIS/eCrisSearch.

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Participation Rates (2006–2018).”

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Participation Rates (2006–2018).”

- “Source of Contributions (2006–2018),” State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, https://seec.ct.gov/Portal/eCRIS/eCrisSearch.

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”

- “Source of Contributions (2006–2018),” State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, https://seec.ct.gov/Portal/eCRIS/eCrisSearch.

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”

- State of Connecticut State Elections Enforcement Commission, “Source of Contributions (2006–2018).”

- Peter Quist, “Connecticut Public Funding Impacts Participation by Special Interests,” last modified October 6, 2017, https://www.followthemoney.org/research/blog/connecticut-public-funding-impacts-participation-by special-interests.

- Peter Quist, “Connecticut Public Funding Impacts Participation by Special Interests,” last modified October 6, 2017, https://www.followthemoney.org/research/blog/connecticut-public-funding-impacts-participation-by special-interests.

- Mark Pazniokas, “Common Cause Uses New Poll to Rally Support for Public Financing of Campaigns, CT Mirror, January 27, 2010, https://ctmirror.org/2010/01/27/common-cause-uses-new-poll-rally-support-public-financing campaigns/.

- Mark Pazniokas, “Common Cause Uses New Poll to Rally Support for Public Financing of Campaigns, CT Mirror, January 27, 2010, https://ctmirror.org/2010/01/27/common-cause-uses-new-poll-rally-support-public-financing campaigns/.

- Connecticut—Reclaiming Democracy: The Inaugural Run of the Citizens’ Election Program for the 2008 Election Cycle, State Elections Enforcement Commission, October 2009, https://seec.ct.gov/Portal/data/Publications/ Reports/2008_cep_report_reclaiming_democracy_102709.pdf.

- Connecticut—Reclaiming Democracy: The Inaugural Run of the Citizens’ Election Program for the 2008 Election Cycle, State Elections Enforcement Commission, October 2009, https://seec.ct.gov/Portal/data/Publications/ Reports/2008_cep_report_reclaiming_democracy_102709.pdf.

- Jonathan Pelto, “Public Hearing Citizens’ Election Program,” Post Reporting Service, November 19, 2008.

- Jonathan Pelto, “Public Hearing Citizens’ Election Program,” Post Reporting Service, November 19, 2008.

- “CT Bottle Bill Redemption Data,” State of Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, 2019, https://www.ct.gov/deep/Lib/deep/reduce_reuse_recycle/bottles/bottle_bill_data_-_thru_Q1_2019.pdf.

- Chris Caruso, “Election Fund Is Keeping Government Honest,” Hartford Courant, May 8, 2009.

- “CT Bottle Bill Redemption Data,” State of Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection, 2019, https://www.ct.gov/deep/Lib/deep/reduce_reuse_recycle/bottles/bottle_bill_data_-_thru_Q1_2019.pdf.

- Chris Caruso, “Election Fund Is Keeping Government Honest,” Hartford Courant, May 8, 2009.

- “Competitiveness,” Follow the Money, 2019 https://www.followthemoney.org/tools/ci#y=2018&c-r ot=S%2CH&ffcgo=1&c-r-tc=1.

- “Competitiveness,” Follow the Money, 2019 https://www.followthemoney.org/tools/ci#y=2018&c-r ot=S%2CH&ffcgo=1&c-r-tc=1.

- Follow the Money, “Competitiveness.”

- Follow the Money, “Competitiveness.”

- T. Swan, Campaign Finance Reform Panel (New Britain, CT: Center for Public Policy and Social Research, Central Connecticut State University, 2017), https://mediaspace.ccsu.edu/media/Campaign+Finance+Reform/1_km33393f.

- T. Swan, Campaign Finance Reform Panel (New Britain, CT: Center for Public Policy and Social Research, Central Connecticut State University, 2017), https://mediaspace.ccsu.edu/media/Campaign+Finance+Reform/1_km33393f.

- “Women in State Legislatures for 2018,” National Conference of State Legislatures, last modified June 28, 2018, https://www.ncsl.org/legislators-staff/legislators/womens-legislative-network/women-in-state-legislatures for-2018.aspx.

- “Women in State Legislatures for 2018,” National Conference of State Legislatures, last modified June 28, 2018, https://www.ncsl.org/legislators-staff/legislators/womens-legislative-network/women-in-state-legislatures for-2018.aspx.

- DeNora Getachew and Ava Mehta, eds., Breaking Down Barriers: The Face of Public Financing (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2016), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Faces_of_ Public_Financing.pdf.

- Getachew and Mehta, Breaking Down Barriers.

- DeNora Getachew and Ava Mehta, eds., Breaking Down Barriers: The Face of Public Financing (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2016), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Faces_of_ Public_Financing.pdf.

- Getachew and Mehta, Breaking Down Barriers.

- L. Cafero and J. McKinney, Campaign Finance Reform Panel (New Britain, CT: Center for Public Policy and Social Research, Central Connecticut State University, 2017), https://mediaspace.ccsu.edu/media/ Campaign+Finance+Reform/1_km33393f.

- Cafero and McKinney, Campaign Finance Reform Panel.

- L. Cafero and J. McKinney, Campaign Finance Reform Panel (New Britain, CT: Center for Public Policy and Social Research, Central Connecticut State University, 2017), https://mediaspace.ccsu.edu/media/ Campaign+Finance+Reform/1_km33393f.

- Cafero and McKinney, Campaign Finance Reform Panel.

- Peter Applebome, “Connecticut Hopefuls Flock to Public Financing,” New York Times, October 23, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/23/nyregion/connecticut/23towns.html.

- Peter Applebome, “Connecticut Hopefuls Flock to Public Financing,” New York Times, October 23, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/23/nyregion/connecticut/23towns.html.