National Popular Vote is a constitutional and practical way to implement nationwide popular election of the President — a goal traditionally supported by an overwhelming majority of Americans

How does the system currently work?

Right now, the President of the United States is not elected by a popular vote. Instead, each state and Washington D.C. is assigned a certain number of electoral votes based on its population. And in all states but Maine and Nebraska, the candidate who receives the most votes in that state is awarded all of its electoral votes, whether the split is 51% to 49% or 99% to 1%. A majority of 270 electoral votes is required to elect the president.

What are the problems with this system?

The Electoral College is very undemocratic and riddled with issues. For example:

- The candidate who placed second in the popular vote was elected in 2016, 2000, 1888, 1876, and 1824.

- A shift of a relative handful of votes in one or two states would have elected the second-place candidate in six of the last 12 presidential elections.

- The votes of those who do not live in closely divided “battleground” states effectively count less.

- Presidential candidates have no reason to poll, visit, advertise, organize, or campaign in states that they cannot possibly win or lose; in 2016, 68% of presidential campaign visits took place in just six states.

- Voters in “spectator states,” including five of the nation’s 10 most populous states (California, Texas, New York, Illinois, and New Jersey), and 12 of the 13 least populous states (all but New Hampshire) have no real incentive to go to the polls as their votes do not affect the outcome of the election.

How would National Popular Vote work?

States already have the power to award their electors to the winner of the national popular vote, although this would be disadvantageous to the state that did so unless it was joined simultaneously by other states that represent a majority of electoral votes. Hence, the National Popular Vote plan is an interstate compact— a type of state law authorized by the U.S. Constitution that enables states to enter into a legally enforceable, contractual obligation to undertake agreed joint actions, which may be delayed in implementation until a requisite number of states join in.

Under the National Popular Vote plan, the compact would take effect only when enabling legislation has been enacted by states collectively possessing a majority of the electoral votes: 270 of 538 total.

Once effective, states could withdraw from the compact at any time except during the six-month window between July 20 of an election year and Inauguration Day (January 20).

To determine the National Popular Vote winner, state election officials simply would tally the nationwide vote for president based on each state’s official results. Then, election officials in all participating states would choose the electors sworn to support the presidential candidate who received the largest number of popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The winner would receive all of the compact states’ electoral votes, giving them at least the necessary 270 to win the White House. The National Popular Vote compact would have the same effect as a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College but has the benefit of retaining the power to control presidential elections in states’ hands. This feature is critical to the passionate bipartisan support the compact receives.

What are the advantages of National Popular Vote?

- Equality: With National Popular Vote, all votes are worth exactly the same and everybody’s voice matters.

- Fairness: This compact would rightfully ensure that the candidate who receives the most votes wins, just as in any other election in the country and unlike in 2000 and 2016.

- Accountability: Because the National Popular Vote plan would create a supermajority for the national popular vote winner, candidates would be accountable to all Americans and not just to those in battleground states.

- Motivation: This reform gives voters in all states, regardless of party affiliation, an incentive to vote in presidential elections and would help build GOTV efforts in all states

- Accuracy and Security: With a single, massive pool of 122,000,000+ votes, there is less opportunity for a close outcome or recount with National Popular Vote than with 51 separate smaller pools, where a few hundred popular votes can decide the presidency. For example, President Bush in 2004 had a decisive, 3.5 million vote lead over John Kerry; yet with a shift of only 60,000 votes in Ohio, Kerry would have won the election. Similarly, the disputed 2000 presidential election was an artificial crisis created by Bush’s 537-vote lead in Florida in an election in which Al Gore had a 537,179-vote lead nationwide (1,000 times greater).

- Finality: The electoral vote majority provided under the National Popular Vote plan would also eliminate the possibility of a presidential election being thrown into the House of Representatives (where each state would have one vote, regardless of its population) and the vice-presidential election being thrown into the U.S. Senate because of a tie vote among electors.

How many states are currently signed on?

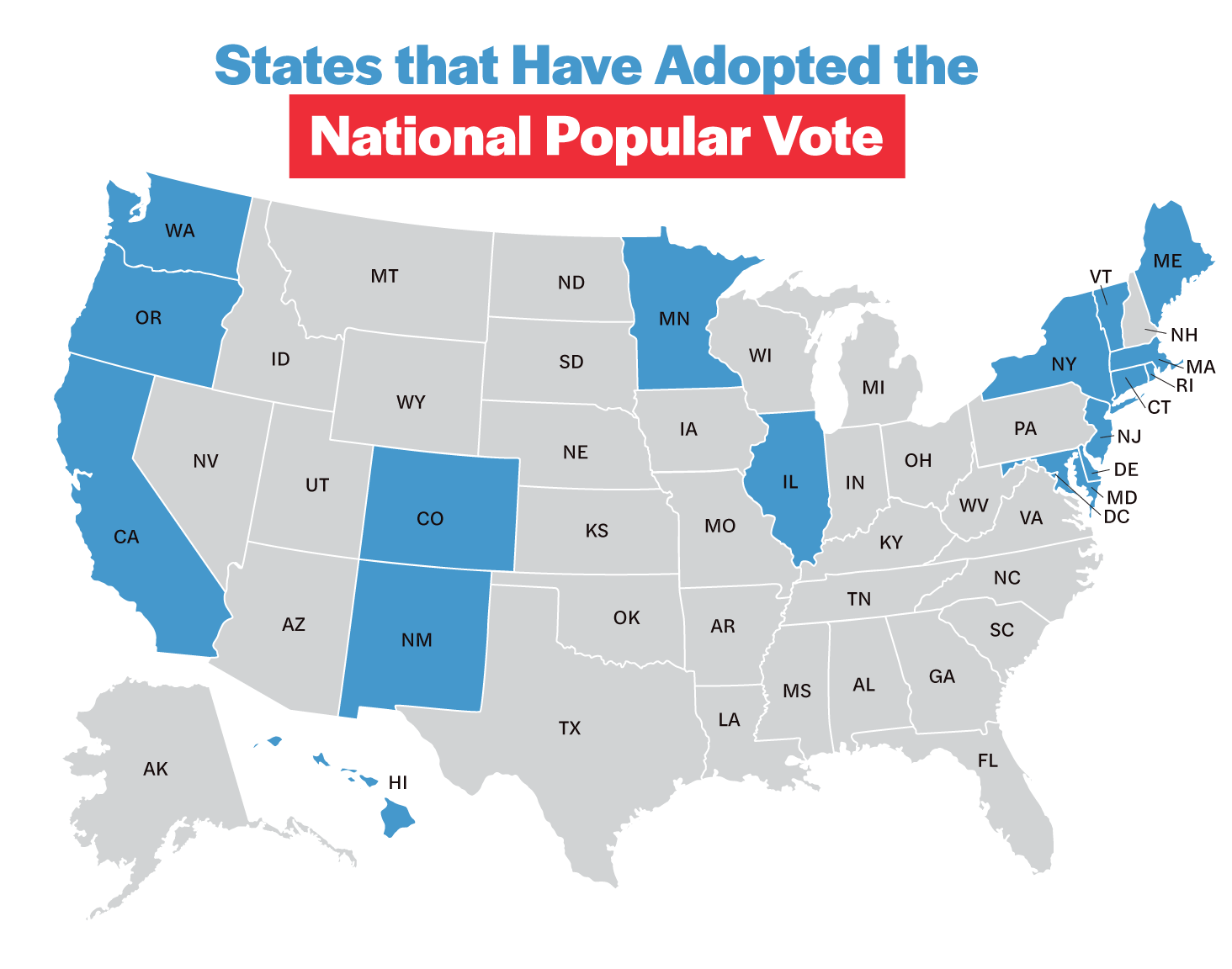

As of now, 17 states and Washington, D.C. have joined the National Popular Vote compact: Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maryland, Washington, New Jersey, Illinois, New York, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Delaware, Maine and Oregon. This brings us to 209 of the 270 (73%) electoral votes needed to activate the pact — just 65 votes away.

Wouldn’t this mean that candidates would only need to campaign in big cities?

Although it is sometimes conjectured that a national popular election would focus only on big cities, it is clear that this would not be the case. Evidence as to how a nationwide presidential campaign would be run can be found by examining the way presidential candidates currently campaign inside battleground states. Inside Ohio or Florida, to pick two examples, the big cities do not receive all the attention, and they certainly do not control the outcome. Because every vote is equal inside Ohio or Florida, presidential candidates avidly seek out voters in small, medium, and large towns. The itineraries of presidential candidates in battleground states (and their allocation of other campaign resources) demonstrate what every gubernatorial or senatorial candidate in every state already knows — namely that when every vote matters, the campaign must be run in every part of the state.

Is it constitutional?

Yes. The selection of presidential electors is specifically entrusted to the states by the Constitution. As with other powers entrusted to the states, it is an application, not a circumvention, of the Constitution when the states utilize those powers as they see fit. The framers enacted the provisions relating to the Electoral College to allow for state innovation. In contrast, other issues related to the federal government are not exclusively entrusted to the states, and therefore the states lack the power to alter them.