Is “one person, one vote” really controversial? The case for the National Popular Vote

It’s hard to definitively call any one pro-democracy initiative “the answer” to the flaws in our modern political system. At Common Cause, we like to say there’s no silver bullet reform for our democracy. The influence of the wealthy and connected persists at all levels of our government, as do racially- and politically-motivated gerrymandering throughout the country—and they aren’t an easy fix.

But for the complexities and nuance provided by issues from automatic voter registration to publicly-financed elections (ones we at Common Cause will engage in relentlessly), the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPV) cuts through the noise with a clear solution to a real problem.

If NPV sounds like a foreign concept, allow me to briefly explain.

Since the dawn of democracy in our country, the president has not been elected by the popular vote. Instead, the Electoral College has blocked Americans from having a direct say in who runs the highest office in the land.

According to the Constitution, members of the Electoral College select the president and vice president of the United States. But the Constitution never specified who those electors were–giving state legislatures the power to choose whoever they wanted without input by the people.

That system has evolved in the last 200 years leading to today’s system of winner-take-all elections. If a candidate wins a simple majority in a state, then 100 percent of the electoral votes in that state go to them, regardless of whether they win with one vote or with one million votes. That’s how it works in 48 states. Two states, Maine and Nebraska, award their electoral votes by congressional district.

While some believe a Constitutional amendment to disband the Electoral College is the right way to go, such an approach is not necessary to enact the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

Under the NPV compact, states agree to award their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote nationally. Because a candidate needs 270 electoral votes to win an election, National Popular Vote would kick in once states adding up to that 270 join the compact.

That means no more 1 percent victories in a handful of swing states deciding the winner. No more campaigns which ignore half of the country because the “electoral math” tells them they can. No more victories for candidates who don’t have the support of the whole country.

“No American should be a spectator of democracy”

Two-thirds or more of Americans live in so-called “spectator states,” which include large states like California and Texas, as well as 12 of the 13 least-populous states. Why? Because it doesn’t make sense for candidates to campaign and spend in states that are a guaranteed win or loss under the current system. Those reliably “red” and “blue” states are left out of the process—while voters in a handful of “swing” states are left to pick who is president. Those states determine elections for no other reason than their even balance between Democrats and Republicans. We believe no American should be a spectator of democracy.

With the National Popular Vote, all votes are worth the same. The candidate who gets the most votes wins. Candidates will even be forced to take the drastic step of paying attention to those Americans in “spectator states,” bringing more people into the fold and leading to policies and plans that take everyone into account.

So with all the facts straight, what’s actually being done to make the National Popular Vote a reality? The answer: a lot.

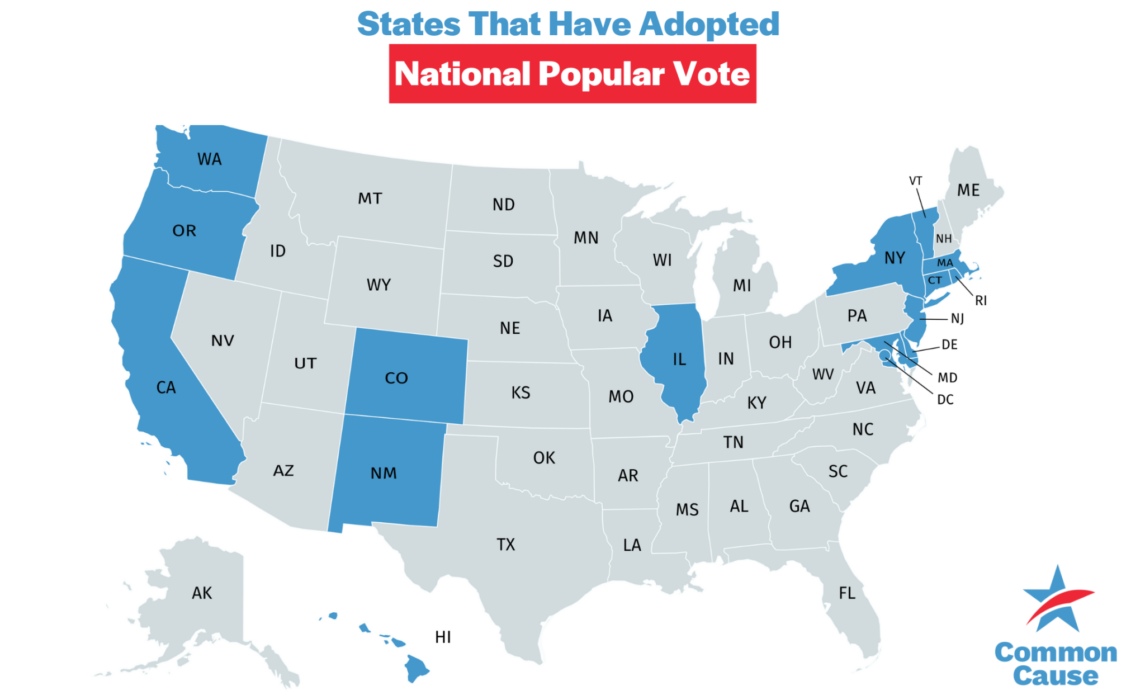

Fifteen states and Washington DC have all approved the NPV Interstate Compact. They account for 195 votes in the Electoral College, meaning another 74 would make NPV a reality.

The path to 270 could come about in several ways. Texas + Arizona + North Carolina + Missouri = National Popular Vote. Pennsylvania + Minnesota + Georgia + Florida = a fairer democracy. So-called “swing states” don’t control the keys to a win—huh, just like a popular vote. Do the math for yourself below if you don’t believe me.

Regardless of the wonky “what if” game we can play with states that may pass laws to join NPV, the point of the compact itself is simple. The presidential candidate that wins the most votes wins the election. Four states joined the compact in this past year alone, as Colorado, Delaware, New Mexico, and Oregon became the latest states to sign on to the compact to take it over 70 percent of the way to the 270 votes needed. Today, the movement is closer than ever.

In a political system made complicated by unlimited money, gerrymandered maps, and out-of-control lobbying, NPV is simple. Let’s finally embrace one-person one-vote and pass this simple and effective reform.