Running for Baltimore (2017)

Donors appear to play by their own rules, either exploiting loopholes in Maryland’s campaign finance law — or violating it altogether.

The cost to run for office in Baltimore City rises

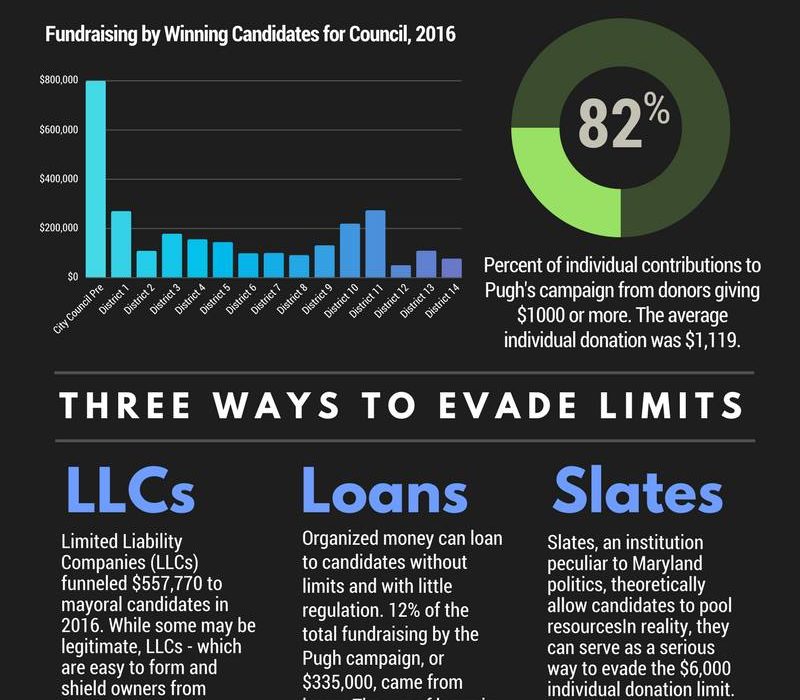

The cost to run for office in Baltimore City rose steeply in the last five years — 25% for the mayor’s race, and over 50% for council races, according to research released by Common Cause Maryland. This spike was true of both the mayoral race, where winner Catherine Pugh raised nearly $280,000, and council races, where the average candidate raised over $185,000.

“This spike in campaign costs is both a reflection of the changing campaign landscape and a call to action for stronger state laws and enforcement,” said Aaron Boxerman, Research Associate for Common Cause Maryland.

According to the analysis, the increase in funds is not coming from growth in the number of small-dollar donors, but rather a staggering increase in the average donation to mayoral campaigns. The average donation size to winning mayoral candidates increased from $525 in 2007 to $681 in 2011, then nearly doubled to $1,119 in 2016. In other words: wealthy donors are donating more, whether as individuals, from businesses, or through PACs.

Consider some of the biggest players in the 2016 Baltimore mayoral race: an empty building in Lanham, MD from which several companies — some bankrupt, few with any internet presence — ostensibly operate; a shell company in downtown Baltimore’s Little Italy; and unregistered corporations with no public records funneling thousands of dollars to candidates from P.O. boxes in Timonium. Analysis by Common Cause Maryland revealed that these donors appear to play by their own rules, either exploiting loopholes in Maryland’s campaign finance law — or violating it altogether.

“The continued growth in LLC spending in campaigns was surprising, given that legislation in 2013 treating LLCs as single entities was widely expected to decrease their expenditures,” explained Boxerman. “This creates two concerns: first, that LLCs that share common ownership or control are not obeying the law and continue to donate above the legal limits; and, second, that individuals are creating fake LLCs for the intent of making campaign donations, which is strictly illegal under campaign finance law.”

LLCs were not the only entities whose activities in the election were questioned. Loans, slates, and entities making expenditures independent from candidates all played a role in the election.

“While this report identifies some specific cases that raised red flags, it primarily documents loopholes in Maryland campaign finance law and suggests reforms,” Boxerman said. “We’re less concerned that the law has been broken. We’re concerned that the law itself is broken; that organized money can legally evade the intent of past legislation because of loopholes and poor enforcement.”

“If past is prologue, the troubling trends in the city elections of 2016 will certainly play out in the statewide elections in 2018,” said Jennifer Bevan-Dangel, executive director of Common Cause Maryland. “We urge the state legislature to move a package of reforms that would help check the influence of special interests and ensure our democratic institutions are responsive and accountable to the people.”