Report

Report

Zero Disenfranchisement: The Movement to Restore Voting Rights

Related Issues

Introduction

Felony disenfranchisement laws prohibit people with felony convictions from voting in elections. These restrictions have been a part of U.S. law since the inception of our nation. Depending on the state, the law may prohibit someone from voting years after they have completed their sentence. For the most part, these laws have been used to suppress the voices of vulnerable communities.

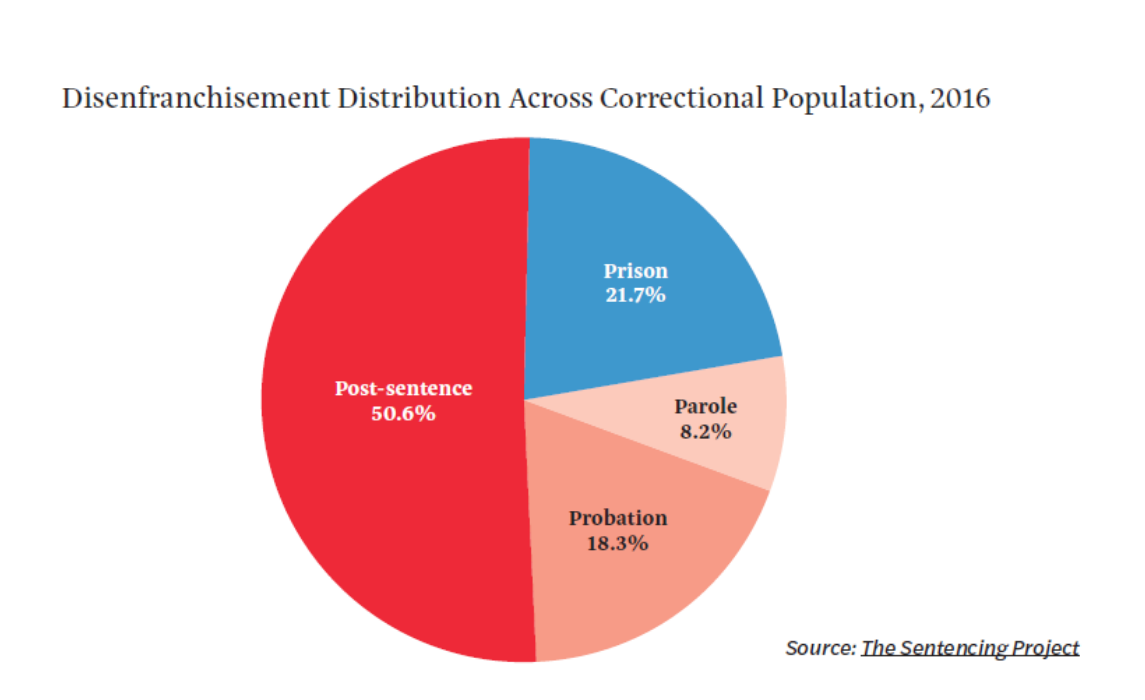

According to the Sentencing Project, as of 2016, an estimated 6.1 million people are disenfranchised in the U.S. because they have a felony conviction.1 In 2016, about 50% of that population had already completed their sentences. Furthermore, approximately 1 out of 40 U.S. adults is disenfranchised.

The Restoration of Voting Rights Movement — a movement of activists, nonprofits, and other organizations— is gaining great momentum in the fight to restrict and end the use of felony disenfranchisement laws throughout the U.S. In 2019, felony disenfranchisement is finally a major topic in the media and among presidential candidates. Many activists, advocates, and grassroots and community organizers have been tackling this issue for years; however, until now, felony disenfranchisement has taken a back seat to other issues in the media. In the latest surge of progress, about 130 bills restoring voting rights were introduced in 30 state legislatures this year, and at least four of those states considered allowing incarcerated people to vote. Thus, it has become more difficult for politicians to avoid taking a position on the issue.

In April 2019, Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders announced his position that anyone with a felony conviction, including those who are currently incarcerated, should have the right to vote. Because he comes from Vermont, one of two states in the U.S. that has always allowed incarcerated people to vote, Sander’s position made sense. Stating that “voting is inherent to our democracy … Yes even for terrible people,” he ignited a discussion among other presidential candidates. Most either took the stance of supporting only voting rights for formerly incarcerated people or stated that they were open to the idea of voting rights for currently incarcerated people, without taking a hard stance.”5 The viewpoint of Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg is another that stands out. Buttigieg is strongly opposed to voting rights for currently incarcerated people, but supports voting rights for formerly incarcerated individuals. He has stated that the revocation of voting rights is part of criminal

punishment and that voting rights should not be treated as an exception to punishment.6

The viewpoint shared by Buttigieg is common amongst many Americans. In a 2018 poll, researchers found that 24% of U.S. adults support restoring voting rights to people while they are in prison, and 58% are opposed. So while it seems Americans’ opinions on re-enfranchisement have come a long way in the

past twenty years, the polls show many Americans have not accepted the idea of restoring voting rights to people who are currently incarcerated.

Felony disenfranchisement laws are antiquated and have a disgraceful past. These laws not only have a disproportionate impact on communities of color and low-income communities, but also have no criminal deterrent or rehabilitative value. The increase in attention being paid to felony disenfranchisement laws warrants a serious overview of felony disenfranchisement in the U.S. This report will discuss the history of felony disenfranchisement laws and their impact on our society, analyze the arguments surrounding felony disenfranchisement laws, and explore the movement to restore voting rights to people with felony convictions. This report also concludes with recommendations for states and advocacy groups interested in starting work in the Restoration of Voting Rights Movement.

The History of Felony Disenfranchisement

Before and After the Civil War

Our democracy has been susceptible to bias and discrimination since its founding. Many states — not just Confederate states — used felony disenfranchisement laws and other racist laws to dilute the voting power of the black populace after the Civil War.

Before the Civil War, most states had some form of disenfranchisement laws on the books, but the laws were narrow and applied to a few select crimes.8 State laws regarding felony disenfranchisement were not as harsh as they are today. However, after the Civil War — and after the passing of the 15 Amendment— new disenfranchisement laws were significantly broader, extending to all felonies.9 After the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were passed, giving black people human and civil rights. The 15 Amendment in particular endowed the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”10 The 15th Amendment gave black men the right to vote — and it took another 50 years for black women to obtain voting rights with the passage of the 19th amendment. In a society that had known black people only as slaves or less than human, efforts were made to resist and interfere with these newly given rights. One weapon in states’ arsenals was use of punitive disenfranchisement laws.11

A felony disenfranchisement law is “race neutral” on its face. However, historically, the U.S. has had a biased criminal justice system in which race is tied to criminal punishment.12 By the end of the Civil War, states were already incarcerating black people at a higher rate than they incarcerated white people.13 Many states criminalized black life; seemingly racially neutral laws were selectively enforced by a nearly all white criminal justice system.14 Many of the major actors in the criminal justice system (e.g., law en- forcement, prosecutors, defense attorneys, juries, judges) were all white and free to act in a biased way toward black people. Black people were convicted significantly more than white people, with a very low bar for probable cause.15 The increase in the prosecution of freedmen and felony disenfranchisement laws further limited black suffrage. Policies that restricted voting based on felony conviction were used to criminalize black people and uphold white supremacy.

An example of how felony disenfranchisement laws were used to weaken black voting power can be seen in the legislative history of Alabama. In 1901 Alabama held a constitutional convention. The convention president, John Knox, stated in his opening address that the purpose of the convention was to establish white supremacy.16The plan to establish white supremacy involved “subvert[ing] the guarantees of the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments without directly provoking a legal challenge.”17 By doing so, the state could still discriminate against black people without being in violation of federal law by denying voting rights or citizenship. The convention attendees decided that an effective way to interfere with these rights was with felony disenfranchisement laws, or laws that prohibit a person from voting because they have been convicted of a felony.

The idea was simple. If Alabama broadened its felony disenfranchisement law to include more crimes, then voting rights could be revoked in a seemingly nondiscriminatory way, especially since it was fairly easy to arrest and convict black men with little probable cause. The delegate who introduced the felony disenfranchisement provision, John Fielding Bums, stated, “the crime of wife-beating alone would disqualify sixty percent of Negroes.”18 The general phrase “moral turpitude” and crimes such as vagrancy, living in adultery, and wife-beating were all chosen for implementation of the law to target black people.19 The convention attendees concluded that the “justification for whatever manipulation of the ballot that has occurred in this State has been the menace of negro domination.20 This strategy of discriminating against blacks by targeting “characteristics” or circumstances associated with black people would continue throughout the Jim Crow era.

Disenfranchisement laws have a racially tainted legacy that calls into question whether these laws would exist if not for the abolishment of slavery and the subsequent granting of voting rights to black people. Overall, these laws were designed to weaken the voting power of communities of color. The combination of states implementing criminal laws designed to target black voters and states implementing broad disenfranchisement laws that revoked voting rights upon the conviction of a felony had the desired effect of keeping black people from voting in elections.21

Disenfranchisement laws have a racially tainted legacy that calls into question whether these laws would exist if not for the abolishment of slavery and the subsequent granting of voting rights to black people.

Attempts have been made to argue that felony disenfranchisement is unconstitutional because of its racist history. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has interpreted section 2 of the 14th Amendment as permitting states to deprive individuals of their fundamental right to vote if they have been convicted of a crime. In the case of Richardson v. Ramirez, the court held that a state may strip people with felony convictions of their fundamental right to vote without violating the 14th Amendment, even if the individual has already served their time. Such laws, in the court’s view, simply did not warrant the same level of scrutiny as other restrictions on the vote.

The Impact of the “War on Drugs” on Felony Disenfranchisement

In addition to early efforts to keep black people from voting, the “war on drugs” has magnified the issue. The “war” was and is a campaign led by the U.S. government to criminalize the use of drugs — such as marijuana and smokable crack cocaine — and implement drug policies intended to discourage drug production, distribution, and consumption.22 The “war on drugs” began in the 1970s and peaked in the ’80s and ’90s. This campaign against drug use led to high arrest and conviction rates that have played a central role in the 500% increase in the prison population over a 40-year period.23 There are currently 2.2 million people in prison or jail in the U.S.24 High arrest and incarceration rates are not reflective of increased drug use, but rather of law enforcement’s focus on urban areas, lower-income communities, and communities of color.25

Not only does the drug war drive extreme rates of imprisonment, known as mass incarceration, it also has a disparate impact on people of color, increasing racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system.26 The drug war has a disparate impact on black and brown communities because of racial discrimination by law enforcement. The “war on drugs” further exacerbates the disproportionate impact of felony disenfranchisement on black people, because these drug convictions lead to people having their voting rights revoked. This domino effect caused by institutional racial bias warrants a high level of scrutiny and reform.

The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement

According to the Sentencing Project, as of 2016, an estimated 6.1 million people are disenfranchised in the U.S. because they have a felony conviction.27 In 2016, about 50% of that population had already completed their sentences. Furthermore, approximately 1 out of 40 U.S. adults is disenfranchised.28

One issue with felony disenfranchisement laws is the confusion and administrative hassle they generate. There is no federal felony disenfranchisement law; each state has its own version. For instance, in Maryland, voting rights are restored upon release from prison. However, in Nebraska, voting rights are restored two years after the end of one’s sentence. The confusing information among states can be difficult for people with felony convictions, who have to relearn what their rights are. Also, election officials, who are tasked with keeping voter rolls updated, have the additional task of removing the names of people who have been incarcerated.

One issue with felony disenfranchisement laws is the confusion and administrative hassle they generate.

Sometimes, there are errors, and the wrong people are purged from voter rolls.29 These obstacles further complicate the restoration of voting rights.

The debate regarding felony disenfranchisement has also drawn attention to the fact that many states allow districts that contain prison facilities to count incarcerated people for redistricting purposes. Most of the time, these districts are majority white and rural. Therefore, these districts are benefiting from the presence of incarcerated people, while those incarcerated people are prohibited from voting in a phenomenon known as prison gerrymandering. Prison gerrymandering gives an unfair advantage to districts where prison facilities are located and dilutes the voting power of communities where incarcerated people have their primary addresses — all while incarcerated people are denied the right to vote.

Felony disenfranchisement is an issue relevant to everyone; however, communities of color are impacted the most. Just as black people are disproportionately represented in criminal justice systems across the nation, they are also disproportionately affected by felony disenfranchisement laws. One in 13 black people of voting age is disenfranchised.30 This results in about 7.4% of the black population being disenfranchised, as opposed to 1.8% of the non-black population.31 Black people are disenfranchised at a rate four times greater than their non-black counterparts.32

The reality is that black and brown people are more vulnerable to felony disenfranchisement laws because they are overly represented in the criminal justice system. For example, in New Mexico, a large population of Hispanic people is disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system.33 Because felony disenfranchisement affects people who have felony convictions, the Hispanic population ultimately is largely impacted by felony disenfranchisement laws. Communities of color across the country are seeing the power of their vote weakened.

THE GOOD NEWS

The number of people who are disenfranchised because of a felony conviction is decreasing. Since 2016, there have been reforms in several states that have impacted this number. For example, in Florida, the state passed the Amendment 4 ballot initiative, which restored voting rights to people who have completed their sentences. The Florida Rights Restoration Coalition estimates that under the ballot initiative and subsequent legislation narrowing the scope of the law, 840,000 people had their voting rights restored. Additionally, in Colorado, people on parole are now permitted to vote. And so, the number of people who are disenfranchised because of their felony conviction is decreasing. However, there is still much more work to be done.

Sherri Davis was born and raised in the District of Columbia. She attended DC Public Schools and graduated from The School Without Walls High School. Sherri worked retail management jobs in college  while raising her three children as a single mom. She switched careers to become a teacher to have a schedule closer to that of her children. Sherri worked as a DC Public School teacher for ten years. During which time she was the TEAM (Together Everyone Achieves More) Award Recipient 2008 for most significant gains in reading test scores in DC Public School district. Her classroom was the Special Education Inclusion Model Classroom for the district. She also served as the Washington Teachers’ Union (WTU) Local 6 Building Representative resolving disputes between administrators and teachers.

while raising her three children as a single mom. She switched careers to become a teacher to have a schedule closer to that of her children. Sherri worked as a DC Public School teacher for ten years. During which time she was the TEAM (Together Everyone Achieves More) Award Recipient 2008 for most significant gains in reading test scores in DC Public School district. Her classroom was the Special Education Inclusion Model Classroom for the district. She also served as the Washington Teachers’ Union (WTU) Local 6 Building Representative resolving disputes between administrators and teachers.

Sherri Davis owned Fast Facts Tax Service(2FT) a tax preparation and refund loan company. Sherri single-handedly grew her business to four retail locations and over 5000 clients. She later served a brief stint in prison for her company’s role in mistakes made during her rapid expansion that lead to a tax scheme. During her incarceration she became a “whistle blower” writing various agencies and filing numerous administrative remedies regarding the conditions at Alderson Federal Prison Camp or “Camp Cupcake”.

After her release she had difficulty finding employment because of her criminal conviction. Reentry opportunities for women are limited. She was accepted in the Georgetown University Pivot Program which provides returning citizens with work experience through internships, and the opportunity to become entrepreneurs. Sherri interned at Common Cause where she conducted research and wrote blogs on mass incarceration, felony disenfranchisement, and gerrymandering. She also became a member of the Speakers Bureau where she speaks on her experience with the Judicial system, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons to advocate for change.

BY SHERRI DAVIS

Ever since I was a child I have understood the importance of voting and making your vote count. I grew up in a single-parent household, where my mom voted in every election. It was important to her because she was born in 1939 and lived during the civil rights movement, when African American voters were disenfranchised due to unfavorable racist laws, so it became important to me. As soon as I was old enough, I registered to vote.

Registering to vote was the first thing I did on my 18th birthday. I have even attended breakfast meet and greets with the candidate that I support, and I have voted in every election since, except during the time when I was incarcerated.

When I realized I could not vote while I was incarcerated, I felt as if I was in a nightmare that I couldn’t wake up from. Immediately after arriving to prison, I was exposed to immoral and inhumane policies and practices — like the prison not providing sanitary napkins for free or living in a building with no air conditioning, where temperatures are over 110 degrees inside. I think if prisoners were allowed to vote, these practices would be abolished and/or corrected.

In D.C., voting rights are restored once you are released from prison. When my voting rights were restored, I was relieved, because I felt that I was disconnected from my roots and hometown while I was incarcerated. I couldn’t wait to see who the major players were now, the movers and shakers of my hometown, and what was different. When I was released on November 21, 2017, so much had changed and not all of it was for the better — I couldn’t wait to vote to undo some of the mess.

Being convicted of a felony, you lose so much that even after you have served your time, you endure lifetime consequences and effects. As a formerly incarcerated person, you can’t own a firearm or serve in certain official positions, serve on a jury, volunteer, and, in some cases, obtain rental housing or employment. For several reasons, getting my voting rights restored helped to ease my transition back into society with my new label: felon. The first being that I felt as if I was made whole again. I got my voice back. In prison, your voice isn’t heard. Someone else is speaking for you — it’s their choice. The second reason being in terms of if I am having an issue or problem that I may need for city officials (mayor, city council, etc.) to address, being able to vote is an added cushion that an elected and/or city official will take your issue more seriously, as [you are] their constituent. Also, if I don’t agree with or think that a current policy should be changed and/or a new policy implemented and I can’t vote, I can’t make a difference. I can’t help to make a change.

Being able to vote while I was incarcerated would have made a difference. Being able to vote on issues back home that were affecting my friends and family would have been an additional way to help me stay connected to them and the outside world. One of the main impediments to successful reentry is the inability to adapt to the changes in your home environment. Being able to vote would have kept me abreast of all the changes in my hometown, made me an integral part of facilitating the change, and prepared me for changes. It could have also helped me make an immediate impact on the lives of my friends and family and a future impact on my life once I was released and returning home.

The perceptions that people who are incarcerated should not be allowed to vote and that people who are incarcerated don’t care about voting are both wrong. First, people who are incarcerated are still people, and most won’t be incarcerated forever. There are also all types of extenuating circumstances and situations as to why people are incarcerated. What about people who are in debtors prison, incarcerated only because of unpaid bills? They are still citizens and should be allowed to vote on the very laws that affect them.

Second, the people who are incarcerated probably care more about voting than the average citizen who votes. I know from personal experience that prison populations tend to follow elections very closely because of the hope that the elected official will enact favorable laws for early release or criminal justice reform. Being able to vote in prison would be like a lifeline. During the 2016 election, the ladies and I were glued to the TV in Alderson Federal Prison Camp as if we were voting.

Voting rights restoration will have a huge impact on our society. I think there is still a lot of fear surrounding the restoration of voting rights. I think there is a [school] of thought that giving felons the right to vote will somehow disrupt order and balance. I think people have the misconception that felons voting will decriminalize all crimes and make living in America unimaginable and akin to the modern-day version of “The Purge.” These notions are completely unfounded, as the citizens vote but the elected officials typically draft the bills to be voted on. I believe that every citizen is entitled to the right to be heard, and voting is the instrument to use.

Felony Disenfranchisement Arguments

There are several arguments in favor of felony disenfranchisement. These arguments do not hold up well against the benefits of voting rights restoration. In fact, people in favor of felony disenfranchisement are working against their stated interest in public safety.

One argument states that if given the right to vote, people with felony convictions will vote for pro-crime policies and/or politicians. However, this is not a legitimate fear. More than likely, lawmakers would be more inclined to pay attention to legitimate complaints of bias and mistreatment in the criminal justice and prison systems and the people who have personally been impacted. Also, it is an ill-willed assumption that people who have felony convictions would vote to weaken our criminal justice system. People with felony convictions have families and people they care about whom they want to keep safe. Like everyone else, they want to vote in their best interest. Keeping a group of people from voting because of concern over how the may vote is not the American way. In a democratic society, when one disagrees with a certain group’s policy position, the appropriate response is to develop support for your preferred alternatives, not to silence the opposition.

Another argument posits that felony disenfranchisement is a punishment and crime deterrent. However, revocation of voting rights is not a part of actual criminal sentencing. That is, a judge doesn’t revoke some- one’s voting rights once they have been convicted. Felony disenfranchisement is a general law that applies to someone once they have been convicted, regardless of the crime. Judges are not even required to notify people that their voting rights have been revoked. Therefore, felony disenfranchisement is not a deterrent, because many people do not realize their voting rights have been revoked until after they have already been convicted or released from incarceration.

In addition, disenfranchisement is an arbitrary crime deterrent. Even if people are aware of felony disenfranchisement, it is seen as an additional negative consequence. A criminal sentence is enough to punish someone, considering that it entails being forced to reside in a prison or jail with limited freedom and/or having supervised release into the general population. Naturally, the fear of physical incarceration trumps fear of losing one’s voting rights. The additional revocation of voting rights is not only unnecessary, but also counterproductive to a major component of the criminal justice system: rehabilitation.

In actuality, felony disenfranchisement holds us back as a democratic society. Many countries fully recognize the right of incarcerated citizens to vote. Today, 26 European nations at least partially protect their incarcerated citizens’ right to vote, while 18 countries grant people in prison the vote regardless of the offense.34 In Germany, Norway, and Portugal, only crimes that specifically target the “integrity of the state” or “constitutionally protected democratic order” result in disenfranchisement.35

Research has shown that voting is a type of prosocial behavior and that prosocial behavior helps decrease criminal behavior.36 This is because people who are empowered to vote feel as if they are part of a community and do not want to jeopardize their involvement. Meanwhile, people who are denied their voting rights feel isolated from the rest of society.37 That can result in a disconnect from their community and a distrust in the

democratic process. Studies show there are, “consistent differences between voters and nonvoters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”38 Restoring the right to vote can help lower recidivism, the tendency for a person with a felony conviction to reoffend, making it a valuable tool for reentry. Other prosocial factors that help make reentry successful include access to employment, housing, and other services.39 When reentry is successful, there is a positive effect on overall public safety.

There is a connection between successful reentry after incarceration and increased civic participation. This is something to which our society, especially our policymakers, needs to pay more attention. Restoring the right to vote makes people with felony convictions feel as if they are part of their communities and society. When people start to believe their voice matters, they are more engaged and less likely to risk losing their rights. On the contrary, disenfranchisement and the limiting of resources for currently and formerly incarcerated people have no useful purpose outside of acting as barriers to successful reentry. Disenfranchisement limits full democratic participation by citizens, doesn’t promote public safety, and exacerbates inequality in the criminal justice system.40 By continuing to execute felony disenfranchisement laws, our society is acquiescing to their futility and all of the resulting negative outcomes.

Voting Rights Restoration Momentum

Today, reform is in the air, and it is happening through different avenues of policy reform. This is a very important moment for voting rights restoration. Along with the public, government officials are paying more attention to the history of felony disenfranchisement and the arbitrariness of the laws. What is even greater about this moment is that the reform has bipartisan support, reflecting that voting rights restoration is a nonpartisan issue.

Changes in felony disenfranchisement law are happening all across the country. Since 1997, 23 states have amended their felony disenfranchisement policies to expand voting rights.41 As a result, an estimated

1.4 million people regained the right to vote between 1997 and 2018.42 In 2018, New York’s governor pardoned approximately 35,000 people who were on parole, restoring their voting rights. More recently, in 2019, 130 bills restoring voting rights were introduced in 30 state legislatures, and at least four of those states were considering allowing incarcerated people to vote.43 As of May 2019, Florida’s Amendment 4 ballot initiative and subsequent legislation has resulted in 840,000 formerly incarcerated persons gaining eligibility to vote. In the same month, Colorado restored voting rights to people on parole, a move that would impact voting rights for around 9,000 people.

However, it is important to remember that activists and grassroots organizations in communities largely affected by this issue have been fighting for rights restoration for years. Many have been through the criminal justice system themselves or have family and friends who have gone through the system. This country would not be where it is in terms of reform without them, and any future reform will not be successful without them.

Joseph Jackson is the director of the Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition  (MainePrisonerAdvocacy.org), a group that engages in direct advocacy with the Maine Department of Corrections on behalf of prisoners and their families. Mr. Jackson is also a community liaison with Maine Inside Out (MaineInsideOut.org). Mr. Jackson is a returning citizen, having spent two decades as a prisoner in the Maine Department of Corrections. While incarcerated, Mr. Jackson was a literacy volunteer, a PEER educator, a hospice volunteer, a GED tutor, and an Alternatives to Violence facilitator. He is one of two founders of the Maine State Prison chapter of the NAACP and served on its executive committee in several capacities from 2003 to 2012. While incarcerated, Mr. Jackson earned his associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, with summa cum laude honors, from the University of Southern Maine graduate program at Stonecoast. Mr. Jackson’s recognition in Maine support his tireless efforts to push administrators and legislators for criminal justice reform.

(MainePrisonerAdvocacy.org), a group that engages in direct advocacy with the Maine Department of Corrections on behalf of prisoners and their families. Mr. Jackson is also a community liaison with Maine Inside Out (MaineInsideOut.org). Mr. Jackson is a returning citizen, having spent two decades as a prisoner in the Maine Department of Corrections. While incarcerated, Mr. Jackson was a literacy volunteer, a PEER educator, a hospice volunteer, a GED tutor, and an Alternatives to Violence facilitator. He is one of two founders of the Maine State Prison chapter of the NAACP and served on its executive committee in several capacities from 2003 to 2012. While incarcerated, Mr. Jackson earned his associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, with summa cum laude honors, from the University of Southern Maine graduate program at Stonecoast. Mr. Jackson’s recognition in Maine support his tireless efforts to push administrators and legislators for criminal justice reform.

His 2018 Guardian article highlights his work, and his story is starting to get national attention (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/06/us-prisons-maine-rehabilitation-punishment).

In an interview, Joseph Jackson, director of the Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition, stressed the importance of restoring the voting rights of people with felony convictions and shared his hopeful outlook on the Restoration of Voting Rights Movement.

Mr. Jackson grew up with a fear of voting. “Growing up, voting was not promoted as something positive.’’ The fear was passed down in his family to younger generations. However, through education and a desire for institutions to start understanding the cultural needs of the black community, Mr. Jackson gained an understanding of the importance of voting.

Mr. Jackson is from Maine, where voting rights are not revoked when someone has been convicted of a felony. He describes voting while incarcerated in Maine as a “collaborative experience.” Maine holds voter education and registration drives in prison facilities that coincide with elections. Each party sends representatives to talk to incarcerated people about their party platforms. The criminal justice voter education, registration, and absentee ballot process is overseen by the secretary of state and nonprofit groups, such as the NAACP .

He stated, “I’m very happy with the way things are in Maine. Voting allows incarcerated people to have

- say in a number of areas — say in who elected officials It has a huge impact.”

He believes that giving incarcerated people voting rights will lead to good policy changes, especially in areas such as criminal justice reform. “The ability to vote leads to change,” Mr. Jackson noted. “Incarcerated people can utilize the ability to vote to move policies to focus on rehabilitation and incarcerated people and their family needs, as opposed to excluding incarcerated people and their families.”

When asked about the Restoration of Voting Rights Movement, he stated, “There are a lot of voices out there who are part of the conversation. I see more people speaking up and I see it entering the political landscape. I think that’s the first thing that has to happen.” He added, “I’m seeing signs in different states. It’s [a] hopeful [situation].”

Recommendations

Federal Government

- Congress should end the use of felony disenfranchisement laws on the federal level and restore voting rights to currently and formerly incarcerated people (i.e. implement full re-enfranchisement).

State Governments

- States should repeal felony disenfranchisement laws and restore voting rights to currently and formerly incarcerated people (i.e., implement full re-enfranchisement).

- States need to adopt the Maine and Vermont voting model, which includes never revoking the voting rights of people who have felony convictions and facilitating voting for people who are Maine and Vermont are the only states in the U.S. that allow incarcerated people to vote in elections. In these states, incarcerated people vote using absentee ballots based on the incarcerated person’s primary home address. The prison administrations notify incarcerated individuals of upcoming elections and help them register and cast absentee ballots. Incarcerated people are also educated about their voting rights.

- In states that are not close to passing full re-enfranchisement reform, election officials must actively educate people with felony convictions about what their voting rights are and help them register to vote when they are legally able to register to Whether they have their rights restored immediately after they are released from incarceration or after a two-year waiting period after their sentence has ended, notification of what their voting rights are is very important. States should consider voter education and registration upon release from incarceration, upon the end of a period of parole, and/ or upon the end of a period of probation.

- Nonprofit organizations should be permitted to monitor the voter registration and absentee ballot process of incarcerated individuals and to conduct nonpartisan voter Voting while incarcerated should be an institutionalized and collaborative process by which the department of corrections and election officials work together to facilitate voting. Not only should states permit advocates and nonprofit organizations to be a part of the process, but they should seek their input.

Advocates

- Formerly incarcerated people and communities most impacted by felony disenfranchisement laws should be at the forefront of reform As previously stated, there are organizers, activists, and organizations that have been doing this work for a long time. They don’t just deserve a seat at the table; they need to run the show.

- Americans deserve a democracy that fosters their ability to vote and holds their elected leaders accountable, regardless of whether they have a felony The practice of disenfranchising people because of a felony conviction should no longer be practiced in the U.S.

Footnotes

1 “6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016,” The Sentencing Project, 2016, available at https://

www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/6-Million-Lost-Voters.pdf

2 Id.

3 Sydney Ember and Matt Stevens, “Bernie Sanders Opens Space for Debate for Voting Rights for Incarcerated People,” New York Times,

April 27, 2019, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/27/us/politics/bernie-sanders-prison-voting.html

4 Id.

5 Id.

6 Veronica Rocha, Dan Merica, and Gregory Krieg, “Buttigieg Says Incarcerated Felons Should Not Be Allowed to Vote,” CNN, April 22,

2019, available at https://twitter.com/CNNPolitics/status/1120535516984881159

7 See Nathaniel Rakich, “How Americans — and Democratic Candidates — Feel About Letting Felons Vote, FiveThirtyEight, May 6, 2019, available

at https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/how-americans-and-democratic-candidates-feel-about-letting-felons-vote/; “Restoration of Voting

Rights,” HuffPost, March 16-18, 2018, available at http://big.assets.huffingtonpost.com/tabsHPRestorationofvotingrights20180316.pdf

8 Erin Kelley, “Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History,” Brennan Center for Justice, May 19, 2017, available at https:// www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Disenfranchisement_History.pdf

9 Id.

10 US Code Service Const. Amend. 15 § 1.

11 Id.

12 Marc Mauer, “Voting Behind Bars: An Argument for Voting by Prisoners,” The Sentencing Project, 2016, p. 560, available at https://www. sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Voting-Behind-Bars-An-Argument-for-Voting-by-Prisoners.pdf

13 Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, New York: Anchor Books, 2009, p. 53.

14 Id.

15 Id.

16 Id.

17 Underwood v. Hunter, 730 F.2d 614, 619 (11th Cir. 1984).

18 Underwood, 730 F.2d at 620 (citing J. Gross, Alabama Politics and the Negro, 1874-1901 244 [1969]). 19 Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222, 232 (1985).

20 “Official Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Alabama: Day 2, May 22nd,” Alabama Legislature, available at http://www.legislature.state.al.us/aliswww/history/constitutions/1901/proceedings/1901_proceedings_vol1/1901.html

21 Erin Kelley, “Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History,” Brennan Center for Justice, May 19, 2017, available at https:// www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Disenfranchisement_History.pdf

22 “A Brief History of the Drug War,” Drug Policy Alliance, available at https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts/

23 “Criminal Justice Facts,” The Sentencing Project, 2019, available at https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts/

24 Id.

25 “Race and the Drug War,” Drug Policy Alliance, available at http://www.drugpolicy.org/issues/race-and-drug-war

26 “The Drug War, Mass Incarceration and Race,” Drug Policy Alliance, January 25, 2018, available at http://www.drugpolicy.org/resource/ drug-war-mass-incarceration-and-race-englishspanish

27 “6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016,” The Sentencing Project, 2016, available at https:// www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/6-Million-Lost-Voters.pdf

28 Id.

29 See Jonathan Brater, Kevin Morris, Myrna Pérez, and Christopher Deluzio, “Purges: A Growing Threat to the Right to Vote,” Brennan Center for Justice, 2018, available at https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Purges_Growing_Threat_2018.1.pdf

30 Id.

31 Id.

32 Id.

33 “Support for HB 57 to End Felony Disenfranchisement in New Mexico,” Human Rights Watch, January 28, 2019, available at https:// www.hrw.org/news/2019/01/29/support-hb-57-end-felony-disenfranchisement-new-mexico#

34 Emmett Sanders, “Full Human Beings: An Argument for Incarcerated Voter Enfranchisement,” People’s Policy Project, available at https:// www.peoplespolicyproject.org/projects/prisoner-voting/

35 Id.

36 Christopher Uggen and Jeff Manza, “Voting and Subsequent Crime and Arrest: Evidence from a Community Sample,” Columbia Heights Rights Law Review, 2004, vol. 36, pp. 193-215, available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3887/bffdb10e5006e2f902fcf2a46abaa9efdf46.pdf

37 Guy Padraic Hamilton-Smith and Ma Vogel, “The Violence of Voicelessness: The Impact of Felony Disenfranchisement on Recidivism,” Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, 2015, vol. 22, article 3, 407-431, available at https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?arti- cle=1252&context=blrlj

38 Id.

39 Marc Mauer, “Voting Behind Bars: An Argument for Voting by Prisoners,” The Sentencing Project, June 23, 2011, available at https:// www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Voting-Behind-Bars-An-Argument-for-Voting-by-Prisoners.pdf

40 Id.

41 Morgan Mcleod, “Expanding the Vote: Two Decades of Felony Disenfranchisement Reform,” The Sentencing Project, 2018, available at https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Expanding-the-Vote-1997-2018.pdf?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId= 59298010-0bed-4783-9ade-23e215ad6df4

42 Id.

43 Sydney Ember and Matt Stevens, “Bernie Sanders Opens Space for Debate for Voting Rights for Incarcerated People,” New York Times, April 27, 2019, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/27/us/politics/bernie-sanders-prison-voting.html

Related Resources

Report

Zero Disenfranchisement: The Movement to Restore Voting Rights

Letter

Common Cause Urges South Carolina to Evacuate Prison Inmates in Path of Hurricane Florence

Report