Guide

Report

Whitewashing Representation

Related Issues

Partisan operatives are trying to change how electoral districts are drawn, in a radical effort to undermine our representative democracy. By law, electoral districts must have about the same number of people, and state leaders draw those boundaries based on total population counts. But a group of party leaders at the national and state level have been plotting to draw state legislative and congressional districts based solely on the citizen voting-age population (CVAP)—a move that they believe would be advantageous to white voters and harm areas where more people of color, legal residents, immigrants and children live.

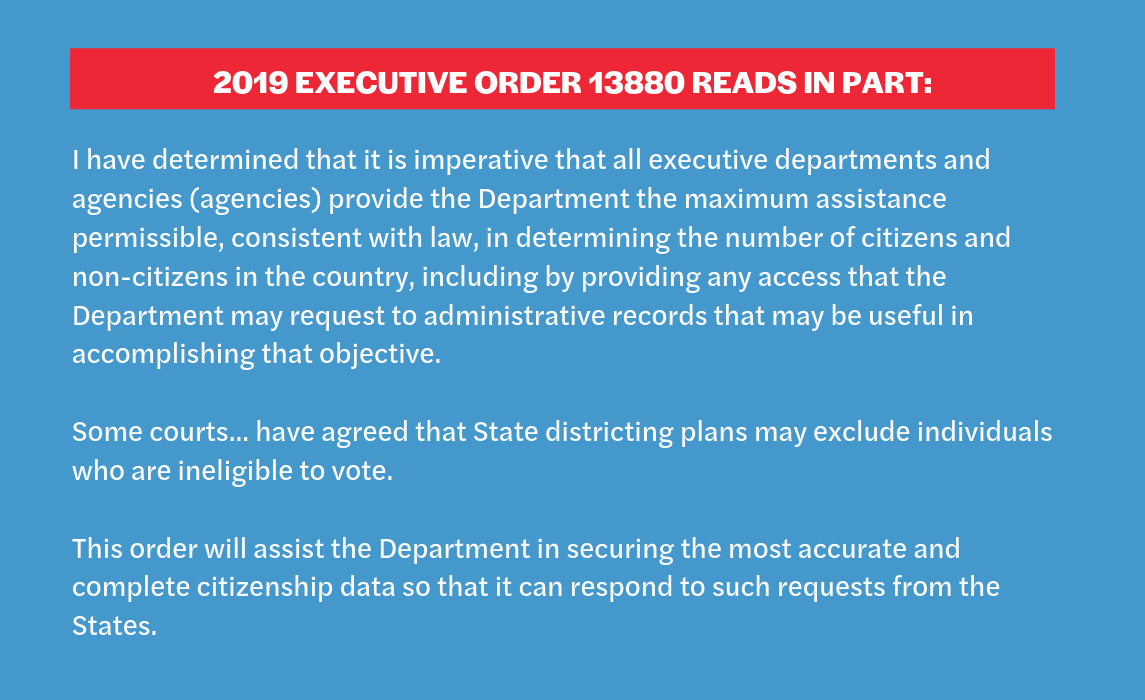

These secret efforts manifested in the Trump Administration’s quest to whitewash our representation by demanding that the 2020 Census include a citizenship question. He abandoned that effort after a U.S. Supreme Court loss and instead issued an executive order demanding several federal agencies provide all their information – that is, administrative data – on citizenship status to the Census Bureau. He ordered the Bureau to combine this administrative data with data from the decennial census and the American Community Survey (ACS) in order to identify non-citizens residing in the United States. The Census Bureau plans to send the aggregate data to states for redistricting.

In recently revealed documents, Dr. Thomas Hofeller, the Republican gerrymandering strategist behind many of the most controversial gerrymandered maps, analyzed and concluded that basing redistricting on citizens aged 18 and over, would “be advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.” He recognized that this move away from using a count of the total U.S. population would be a “radical departure from the federal ‘one person, one vote’ rule” that underlies our representative democracy.

Hofeller stated creating this racial and partisan advantage by removing millions of American residents could only be achieved by collecting citizenship data at the census block level. (More information on the Hofeller Files found here.)

Using citizen voting age data to draw districts will exclude millions of young people and people of color, violates the Constitution and undermines the principles of equal representation that our country strives towards. Understanding the intricacies of what administrative data is, how it is used and what challenges can arise from its use in the 2020 Census gives advocates the tools to fight back.

Takeaways from the report include:

- Administrative data on citizenship should not be merged with 2020 Census data in the redistricting files that are sent to states because the data will be used by partisan operatives to justify skewing electoral districts in a manner that, in the words of Thomas Hofeller, is “advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites”.

- The integrity of the 2020 Census and American Community Survey data should not be tainted by inaccurate and unreliable administrative data on people’s changing immigration status. The administrative data on citizenship will exacerbate the undercount of children and people of color.

- There are significant legal protections that prohibit the sharing and use of census data to target individuals, but there are risks that advocates should be aware and vigilant of.

Have a question that is not answered here? Email Keshia Morris at kmorris@commoncause.org or Suzanne Almeida at salmeida@commoncause.org.

Census Data 101

What is the census and what data does it collect?

The decennial census, conducted every 10 years as required by the U.S. Constitution, is a total count of every person living in the United States at their “usual residence” at the time of the census. Census data is collected primarily through a short-form questionnaire that is sent to every residence in the United States. The form asks about the number of people who live at each location, the race and ethnicity of those people and other very basic data. The aggregate data collected by the census is used for many purposes across business, philanthropic and nonprofit communities, but its primary purpose is to apportion state representation to Congress, to execute state redistricting and to distribute billions of federal dollars.

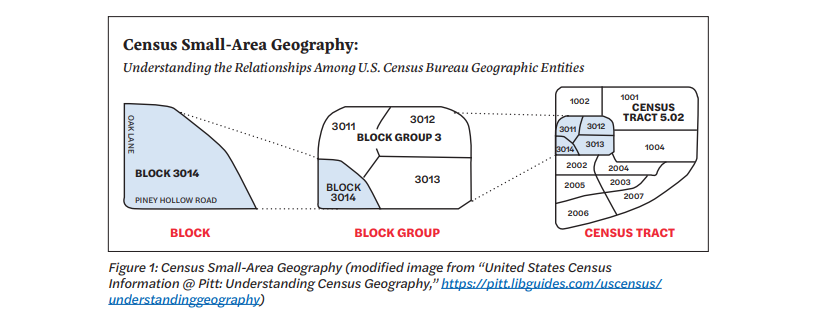

What are census blocks, block groups and census tracts?

The Census Bureau defines three levels of geography. The smallest level, a census block, is a small geographical area bordered by visible features (such as roads, streets, streams and railroad tracks) and invisible features (such as property lines and boundaries for city, township, school district and county). In cities, census blocks can be thought of as a small city block, with streets binding it on all sides. In suburban areas, census blocks can look more irregular and spread out in area, and are bounded by streams, roads and other geographical limits. In more remote areas, census blocks can be a collection of hundreds of square miles of land. An article within a newspaper serves as a helpful analogy to imagine census blocks. Going from a small to wide frame, a newspaper has single articles, sections for different subjects and the entire newspaper itself. A census block is more like a single article, a collection of words bound to that article itself, and its size ranges from large to small. Census blocks are not delineated by their population size. Many census blocks do not have anyone living in them at all, but they generally range from a population of zero to several hundred people per census block. There are about 8.2 million total census blocks in the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

The next largest geography level involves block groups, defined in the Federal Register as “statistical geographic subdivisions of a census tract defined for the tabulation and presentation of data from the decennial census and selected other statistical programs.” Block groups typically contain 600 to 3,000 people, or at least 240 housing units at minimum. Or they contain 1,200 housing units at maximum and are a collection of census blocks. Census block groups may not cross county or state lines, or their geographical equivalent. Block groups are analogous to the sections of a newspaper, which are a collection of articles confined to an area of the newspaper and based on specific subjects. These sections also vary in size, similar to how census blocks vary in size. The United States, including Puerto Rico, has 211,267 block groups.

The largest census geography level is known as a census tract. Tracts are county subdivisions, but they can cross city and town lines. These generally contain 1,000 to 8,000 people and are a collection of block groups. Census tracts are analogous to the newspaper itself. Newspapers vary in length, but they all have articles and sections nested within them.

More information on census geographies

What happens with census data once the Census Bureau receives it?

Once a household fills out its census form either, online, on paper, or over the phone, the Census Bureau encrypts the data and removes all personally identifiable information.

It is then aggregated and run through additional privacy protection algorithms. By the end of the year in which the census is taken, the aggregate data must be sent to the president (for apportionment). By the following April, the aggregate data must be sent to the states (for redistricting).

Census data gathered during the census is used to determine which states gain or lose seats in the House (apportionment), votes in the Electoral College and to redraw congressional, legislative and local districts (redistricting). Census data is also used to allocate hundreds of billions of dollars in federal funding for services, such as health care, education and affordable housing. Businesses rely heavily on the data to make decisions about where to open stores based on population and demographics.

How is apportionment carried out?

Apportionment — or the dividing of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives among the states, based on total population — is the primary purpose of the decennial census. The Census Bureau determines the final apportionment and delivers it to the president through the secretary of commerce. The president provides the final apportionment to Congress by December (and in the case of the 2020 Census, by December 31, 2020).

To create the final apportionment result, the Census Bureau receives, verifies and tallies the data to create a final resident population file. This file is combined with the count of federally affiliated overseas residents (i.e., people who are stationed as military or independent contractors for the federal government). Apportionment calculation formulas are applied to these data and then validated to create the final apportionment results. These results are then independently verified and validated and then used to create the final apportionment tables, which outline the population by state, the corresponding number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and the change since the previous census.

How do states use census data for redistricting?

After each census, states use the aggregate population data to draw legislative and congressional voting districts with relatively equal populations. Federal law contains different equal population requirements for congressional districts and state legislative districts, but the equal population requirements in both cases are driven by what the U.S. Supreme Court has dubbed the “one person, one vote” principle.

“The history of the Constitution, particularly that part of it relating to the adoption of Art. I, § 2, reveals that those who framed the Constitution meant that, no matter what the mechanics of an election, whether statewide or by districts, it was population which was to be the basis of the House of Representatives.” –Supreme Court in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U. S. 9 (1964)

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) states can determine what data they use for redistricting. Twenty-one states have explicit legal provisions that require state legislatures to use only the data from the decennial census to draw districts. Seventeen states have an “implied in practice” reliance on census data. Six states permit the use of census or other data for redistricting, and six states have unique rules about drawing districts.

What data does federal law require to be shared with the states for redistricting?

Under Public Law 94-171, the federal government must transmit population tabulation data obtained in the decennial census to each state for use in state legislative redistricting. Population tabulations are summary tables with the racial, social and economic characteristics of the people who live in a geographic area. The levels of geography that Public Law 94-171 tabulations summarize range from census-defined geographies (e.g., census blocks, block groups and census tracts) to political geographies that states request (e.g., election precincts, wards, and state house and Senate districts).1

The law requires the Census Bureau to provide population data only down to the census block level, but since the start of the Census Redistricting Data Program for the 1980 Census, the Census Bureau has included summaries on larger racial groups,2 cross-tabulated by Hispanic/ non-Hispanic origin and age (18 years old and over).3 The <strong>2010 Public Law 94- 171</strong> summary data also includes information on housing occupancy status, such as whether a housing unit is vacant and whether someone rents or owns the unit. These summaries are calculated at the census block level when possible but are also calculated, upon request from state legislatures, for election precincts, wards, and state house and Senate districts.

President Trump’s executive order requires that citizenship data also be sent to states as apart of the redistricting file. This data will be available down to the census block level, but states may also request the data for other geographic areas.

(Find more information on what is included in the redistricting data file and more information on Public Law 94-171.)

How is citizenship data used in redistricting to enforce the Voting Rights Act?

In most states, citizenship data is not used in drawing maps, but is used to evaluate districts under the Voting Rights Act (VRA) by establishing the citizen voting age population (CVAP). CVAP is the number of people living in a specific area, such as a census block or congressional district, who are citizens aged 18 or older. That data is currently obtained from the American Community Survey (ACS).

Historically, CVAP data from the ACS has been used to determine the size and location of minority populations to ensure compliance with the VRA. Section 2 of the VRA prohibits states and political subdivisions from employing voting practices, standards and procedures that discriminate against any United States citizen on the basis of race, color or religion. Such discrimination includes the drawing of district lines in a manner that dilutes the political power of minority populations.

To establish that a districting plan violates Section 2, the minority group must demonstrate that the plan lacks one or more districts in which the minority group can elect its candidate of choice, despite the fact (1) that “it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district”; (2) that it is “politically cohesive”; and (3) that “the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it … usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate”.4

How do we determine the citizen voting age population?

Currently, citizen voting age population (also referred to as “citizen voting eligible population”) comes from the American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS is conducted by the Census Bureau and utilizes sampling to solicit responses from randomly selected households each year. After the 2000 Census, the ACS replaced elements of the long form census questionnaire with a questionnaire that goes to a smaller sampling of households on an annual basis. The ACS asks respondents about themselves and their communities, including questions about their jobs and occupations, educational attainment, veteran status and rent or home ownership status. Since its conception, the ACS has inquired about citizenship, and race by Hispanic/ non-Hispanic origin.

(Find more information on the American Community Survey.)

Administrative Data 101

What is administrative data?

Administrative data, also known as “administrative records,” involves any records that agencies collect and maintain in order to administer the programs that they run. The Census Bureau website provides an overview of what administrative data is and how it is used for census-related purposes. Such data includes records from federal, state and local governments, and, sometimes, data from commercial entities.

What is the difference between administrative data, survey data from the ACS, and the 2020 Census?

Administrative records are data collected from federal agencies. It includes whatever information that agency collects from people who interact with it. It does not include information from people who have not interacted with the agency.

In contrast, the American Community Survey is a questionnaire that the Census Bureau sends to some households to get a picture of the general population. Unlike the official decennial census, the Census Bureau does not send the ACS questionnaire to every household in the United States. Instead, it sends a detailed questionnaire to a sample of households that have been randomly selected to represent a cross-section of the country — about 1 in 38 households each year. This sample helps us understand the changes taking place across the nation.

The decennial census is special because it is a questionnaire that is administered to every single household in the United States, not just some. Additionally, because the 2020 Census (and any decennial census) questionnaire is administered within a seven month period, it gives a very accurate snapshot of Americans within that time period.

TAKEAWAY: The Census provides us with a snapshot of American demographics

What sources of administrative data will be used to identify citizenship?

President Trump’s executive order listed the following sources:

- Department of Health and Human Services (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Information System);

- Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (national-level file of lawful permanent residents and naturalizations);

- Department of Homeland Security and Department of State Worldwide Refugee and Asylum Processing System (refugee and asylum visas);

- Department of State national-level passport application data;

- Immigration and Customs Enforcement (F1 and M1 non-immigrant visas);

- Customs and Border Protection Arrival/Departure (national-level file of transaction data); and

- Social Security Administration (Master Beneficiary Records).

How will administrative data on citizenship be used in the 2020 state legislative redistricting file?

The Executive Order instructs certain federal agencies to send administrative records to the Census Bureau. Data scientists within the Census Bureau will then work to match data across all databases and combine it with American Community Survey data to create a dataset of people who are and are not citizens. Census Bureau staff will process the matched data to remove all personally identifiable information and to comply with additional data privacy and security measures.

It is unclear whether this information will then be mixed with the existing 2020 Census data tabulations or whether it will be sent as a separate product to the states.

In a recent document, the Census Bureau confirmed that citizenship data will be made available in 2020 redistricting files for “state, county, place, tract, and tabulation block.” In addition, if a state participated in the Redistricting Data Program and worked to synchronize its voting district boundaries (commonly called “precincts’) with census block boundaries, that state may request census numbers for “their congressional, legislative, and voting district boundaries.” Some states do not participate in this program; states like California match the 2020 Census data with their precinct-level voting data through their own state-based programs for redistricting.

The Census Bureau will only release 2020 Census data in what is called “aggregate” form. That is, the 2020 Census data will NOT include information about any one person and will not include data that could personally identify a person. Aggregate data for people in a census block would give information for groups of 200-600 people in an area.

The Census Bureau will never release a report that says, “The family living at 123 Street has people who are non-citizens.”

What does that mean? The Census Bureau will never release a report that says, “The family living at 123 Street has people who are non-citizens.” It may say “In X Census Block, where there are 550 people, 489 people are citizens.”

How has administrative data been used before on the census?

Administrative data has previously been used to aid in counting students and prisoners, to assist in counting people who had not responded to the census (nonresponse follow-up), to update the census Master Address File and to follow up on potentially inaccurate census responses.

Administrative data has also played a major role in assisting other Census Bureau programs for population, economic, income and poverty, and health insurance estimates. It has never been used as the sole source of data collection for demographic information in the way that it is proposed to be the primary source of information on citizenship in 2020.

TAKEAWAY: Administrative records have never been used as the sole source of data collection for demographic information

(Find more information on Census Bureau programs using administrative data, a history of its use in the decennial census and how the Census Bureau uses administrative data at the hyperlinks.)

Data Problems

What types of data problems can occur?

There are three types of problems that can occur when using administrative data.

- Administrative records can be an accurate measure of aggregate trends, but problems arise when they are used to match and count specific household in the census database.5

- Matching data across databases often results in incomplete or mismatched data due to clerical errors, data collection errors or other problems. These issues are more pronounced for non-Anglicized names.

- Administrative data provides data only on individuals who appear in the records, which is likely to lead to a differential undercount caused by undercoverage in the sampling methods.

What matching errors occur with administrative records?

When administrative records are used to match specific individuals or households across different databases, problems arise. People often use different names, nicknames, maiden names or new married names, which makes the process of matching records to survey respondents especially difficult. Additionally, clerical errors in vital information needed for the matching process arise. Birth date and street address records can also be mismatched when the information is incorrectly entered, or people abbreviate or spell elements of their addresses differently.

How accurate are administrative records in capturing data about non-citizen households?

The problem with mismatching administrative records to census respondents is especially pronounced for noncitizen households (households where no member is a U.S. citizen). These households are the hardest to match to records because many noncitizen immigrants do not have the necessary paperwork to provide accurate information on employment, social security or IRS forms.6 Additionally, noncitizens may avoid contact with government agencies altogether, and/or they provide incomplete household information.7 Counting households through administrative data would likely disproportionately undercount noncitizen households.

The problem with mismatching administrative records to census respondents is especially pronounced for noncitizen households (households where no member is a U.S. citizen).

How can undercoverage and overcoverage impact the accuracy of data?

In survey research, coverage refers to how well the population data is captured. Undercoverage occurs when some people or housing units have zero chance at being selected in the sample. Overcoverage occurs when some people or coverage errors in research that examines the broader population are slightly different from those in survey research; they occur when there is incomplete information or records from the broader population.

In the case of the census, undercoverage in administrative records occurs when people in administrative records are not matched to their decennial census responses. This leaves people out of the data that state legislatures and governors receive in their states’ Public Law 94-171 summaries.

Why do coverage errors matter?

Survey research methods select a group of people to study in the hope that the group selected represents the broader population that they come from, rather than attempting to study an entire population. Therefore, coverage errors in survey research may bias the results and inferences made about the population because the sample does not accurately represent the broader population.

Conclusions drawn from data with undercoverage can speak only about who is included in these records, not about the entire population. For example, if someone wants to know what a city thinks about the mayor and they manage to contact every housing unit in the city, they are missing out on what the homeless population thinks about the mayor. In this example, the study captures only what people who occupy a housing unit think, which is problematic because the homeless population’s opinion of the mayor may be directly related to their circumstances and would yield helpful results in assessments of the mayor’s job performance.

In 2010, the Census Bureau found that Census data on White respondents had a 69.7 percent match rate to administrative records, but Hispanics only had a 53.2 percent match-rate, Asian Americans had 67%, Blacks had a 55.2%, and American Indians had 46.4%.

Table 18. 2010 Census Match Study. U.S. Census Bureau

When matching administrative records to census data, is the match rate less for some groups than others?

A 2010 study assessing the accuracy of administrative data linked with the decennial census demonstrated unequal coverage across ethnic groups, with a

stark difference between the match rates of records for Hispanic and non-Hispanic people. Records matched 78.9 percent of Hispanic respondents and 92.2 percent of non-Hispanic respondents from the 2010 Census. The study also indicated that there was undercoverage of the general population, which means that a portion of the population was not counted.

Though using administrative records lowers costs, the conclusions that can be drawn from a study in which the Hispanic-origin population is more likely to be left out than the non-Hispanic origin population are limited. Such limitations can be especially problematic when this data is used for purposes such as Voting Rights Act enforcement or redistricting based on citizen voting age population; in these contexts, these biases influence policy and representation.

While general population undercoverage may make a study inaccurate, it is more likely that a study will be inaccurate when the undercoverage is higher for people with specific demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity or citizenship.

How often do administrative records match census respondents?

The Census Bureau cannot accurately match enough person-address pairs – the combination of a person and an address – with administrative data to generate a complete count of households or individual people. Of the 308.7 million persons-address pairs in the 2010 Census, 30% did not match administrative records. Of the 279.2 million person-address pairs in the 2010 Census that had a unique identifier, nearly a quarter did not match administrative records. If census responses and administrative records do not match, approximately one-third to one-fourth of the population is not correctly captured.

How does administrative data on citizen voting age population compare to that of the American Community Survey?

American Community Survey data has been the source of effective Voting Rights Act enforcement since it was launched in 2005. The overwhelming body of social science research8 confirms that ACS data is more accurate than administrative data.

TAKEAWAY: People of Hispanic origin are more likely to be matched with a wrong address in administrative records. Using incorrect addresses to redistrict Hispanic communities puts them at risk of losing representation.

Census Bureau research identifies significant problems with the accuracy of administrative data. For example, administrative records match respondents of Hispanic origin at a lower rate than non-Hispanic origin.8

Concerns with Data Collection

How has the census historically been used for partisan gain?

United States census is supposed to make sure our government accurately represents our communities. However, history tells us this process can be weaponized for partisan gain. By undercounting people of color, particularly people of African descent, Latinxs and Native Americans have had their voices in government diminished.

Beginning with the first census in 1790, political power was intertwined with the Census and communities of color were deliberately under-counted. In 1790, in order to obtain more political power in the House of Representatives, rural southerners demanded enslaved Africans be counted in the survey, while urban northerners feared their political power would be significantly reduced and diluted. As a flawed compromise and in complete disregard of their humanity, for more than 75 years, enslaved Africans were counted as only three-fifths of a human being for the purposes of Congressional representation and taxation. And for nearly 80 years, Native Americans were completely excluded from the census.

Eventually, the census grew to be more detailed and slightly more inclusive and it became the mission of the census to “count everyone once, only once and in the right place”.

Today, many right wing operatives are attempting to use the census to continue to the tradition of silencing the voices of communities of color. The administration failed in adding a citizenship question to the 2020 Census but is still attempting to wipe millions from political representation by collecting citizenship data from administrative sources to then be used in the redistricting process. Thomas Hofeller, the GOP gerrymandering mastermind, has theorized that redistricting based on the citizen-age voting population would create a structural advantage for “Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites”.

TAKEAWAY: An accurate census is the basis of fair elections. The effort to under count communities of color in the census is an effort to suppress their votes and return to

What are the concerns with citizenship tabulations at the census block level?

There are two primary concerns that advocates and data scientists have with creating citizenship tabulations at the census block level.

First, is privacy: The census is meant to summarize group demographics and protect individuals’ privacy. The smaller the group, the easier it is to identify the people who make up these groups. In 2016, the Census Bureau conducted a study that found that even after personally

identifiable information was removed from census responses, data experts were able to manipulate the data so that individuals or households could be identified by an exact match for fifty percent of people and with “at most one mistake” for ninety percent of people. The bureau is trying to solve this issue of reconstruction with new privacy procedure called differential privacy. However, it is unclear whether this will entirely prevent the match of census data with personally identifiable information. Ensuring that personally identifiable information is confidential is especially important when data such as citizenship is included. Although it is a violation of the Census Act to manipulate census data to identify an individual or to use it for law enforcement, there is a real fear of the consequences of unprotected census data, particularly among immigrant communities of color.

Second, is citizen voting age population (CVAP) redistricting: Politicians who want to manipulate redistricting by excluding noncitizens and anyone under the age of eighteen need data in order to effectively draw gerrymandered maps that can withstand legal challenges. The citizenship data collected and made compatible with the redistricting file sent to states pursuant to the Census Bureau’s directive may provide the necessary quality of data to draw legally sufficient maps. The collection and inclusion of this data is part of a long term strategy by some Republicans to solidify partisan power and exclude people living in the U.S. who are not U.S. citizens and minors from representation.

This would be a major blow to our voting rights and representation in government. Allowing unreliable citizenship data to play a role in redistricting would boost the number of representatives that less diverse communities receive while diminishing the representation of urban, immigrant-friendly areas of equal population. Lawmakers in Texas, Arizona, Missouri and Nebraska have already said that they would consider making use of the citizenship data for redistricting purposes if it became available.

TAKEAWAY: Losing representation means losing a voice in important conversations about resources and policy. Places with more children, immigrants and people of color could hear their voices silenced.

How could the current anti-immigrant environment affect the census and vice versa?

According to prevailing research, heightened immigration enforcement would lead to lower political participation among Latinx and immigrant communities because of the intimidating effect. Though almost all jurisdictions require people to be citizens in order to vote in elections, people who have personal relationships with noncitizens are less likely to interact with government, including participating in the census or in elections. People with unstable immigration statuses are less likely to fill out the census questionnaire because they are less likely to trust the government.10

In a 1995 ethnographic study, one of the respondents had legal citizenship as a student but feared participating in the census because she believed the information could be used to track her down in the future if she lost that legal status. Mixed-status households — households composed of members with different citizenship or immigration statuses (e.g., undocumented immigrants, citizens, legal residents) — are likely to avoid contact with governmental institutions when they suspect it is not safe to do so.11

Heightened “immigration policing” erodes trust in public institutions and forces immigrant communities, including U.S.-born Latinxs who have immigrant parents or feel connected to the immigrant community, to be very selective in deciding when, where and how they engage with public institutions.12 This includes interactions with vital public institutions, such as those involving health care, law enforcement and education.13

While the debate around the inclusion of citizenship data in 2020 may have increased communities’ concern that the data could heighten immigration enforcement in the future, the confidentiality protections currently in place prevent these concerns from becoming reality.

Has census data ever been used to target groups of people by the government?

Census data on race and ethnicity was used to aid in Japanese Internment during World War II and was used again in the 2000s to identify geographies with large Arab ancestry populations under the George W. Bush administration. These data uses were legal at the time of both instances. Notably, confidentiality safeguards have now been adopted to prevent similar census data use in the future, and penalties for this misuse are prohibitively high.14

During World War II, the Department of War coordinated Japanese American internment efforts15 in California, Oregon and Washington using Census Bureau data. The Second War Powers Act of 1942 temporarily lifted data protections that barred the bureau from revealing data linked to specific individuals. The bureau initially admitted to sharing only aggregated population totals so that the Department of War could identify localities to target for its internment efforts. Research later revealed that the bureau also shared personal records for residents of Washington, D.C., who reported Japanese ancestry on the decennial census. This instance of data sharing was legal at the time that it occurred.

In 2004, it was revealed that the Census Bureau shared aggregated totals on Arab ancestry with the Department of Homeland Security. Special tabulations were prepared for law enforcement on Arab Americans from the 2000 decennial census. This action was within the Census Bureau’s authority at the time. One source contains special tabulations on larger cities with over a thousand residents who reported their Arab ancestry in 2000. The other source used ZIP-code-level tabulations in which Arab ancestry was broken down into categories of “Egyptian,” “Iraqi,” “Jordanian,” “Lebanese,” “Moroccan,” “Palestinian,” “Syrian,” “Arab/Arabic” and “Other Arab.” These tabulations were compiled using the responses from the census long-form, which goes to only a sample of census respondents, so tabulations at lower levels of census geography were not necessarily representative of population totals. Requests for special tabulations on sensitive populations made by federal, state or local law enforcement

and intelligence agencies using Title 13 of the U.S. Code (or Census Act) protected data now require prior approval from the appropriate associate director of the government agency.

Under confidentiality protections today, these uses would be deemed illegal, and there would be legal penalties for these violations. There is currently no credible reason to suspect that similar data sharing will happen with the 2020 decennial census data under our current laws, but such violations would face criminal sanctions.

TAKEAWAY: Using census citizenship data for redistricting is an example of legalized, structural discrimination. Using that data for immigration enforcement, however, is illegal.

(Find more information on the census data sharing of Arab-ancestry respondents and Japanese American respondents, and on census privacy and confidentiality protections at the hyperlinks.)

Existing Data Protections

How is data collected from the census protected by the Census Bureau?

Census data from paper responses is reported to the bureau as millions of individual records. Once data is collected, it is processed by Census Bureau staff to remove personally identifiable information. Then it is aggregated and run through additional privacy protection algorithms.

Data from online responses, on the other hand, is immediately converted into a form that cannot be easily understood by unauthorized people. The data is encrypted twice (once after the participant hits “Submit” on the online form and again after responses reach the Census Bureau’s database).

Lists of individuals’ records (microdata) will be housed at the Census Bureau, but the aggregate data are publicly available.

There are also significant legal protections that prohibit the data from being misused or to target individuals for law or immigration enforcement actions.

How is the Census Bureau addressing the possible ‘reconstruction’ of data from Census Bureau statistics?

In 2016, the Census Bureau conducted a study that found that even after personally identifiable information was removed from census responses, data experts were able to re-create the data so that individuals or households could be identified by an exact match for fifty percent of people and with “at most one mistake” for ninety percent of people. This process is known as “reconstruction.”

To address reconstruction issues in the past, the Census Bureau swapped responses from some respondents before releasing the full dataset. In 2020, The bureau will implement a new procedure called differential privacy, which provides “statistical guarantees against what an adversary can infer from learning the results of some randomized algorithm.”16 During this process, random error is introduced to aggregate data to ensure that the chances of guessing a person’s responses accurately are similar to the chances of accurately reconstructing an individual’s actual census responses given all of the aggregate census data that one has access to. That is, a person’s ability to reconstruct individuals’ responses is no better than their ability to guess them without the data. Differential privacy takes into account that some demographic characteristics are less common in certain geographies, so it applies more random error to these people’s responses in the publicly available aggregate tables.

TAKEAWAY: The Census Bureau is making it more difficult to trace census data back to the person who submitted it.

What legal confidentiality protections apply to census and administrative data?

The confidentiality provision of the Census Act (also known as Title 13 of the U.S. Code) provides broad protections for the confidentiality of census data and any administrative data that is combined with the census data. If the Census Bureau or “other federal, state, local, and tribal governmental agencies, as well the private sector,” uses statistical products made from administrative data on citizenship to harm small geographies with large noncitizen populations, those violations are subject to penalties outlined in the privacy protections.17

Confidentiality restrictions on administrative records and on statistical products legally protect populations against targeting by law enforcement.

Neither the Census Bureau nor anyone who works for it may use the information gathered in the census or disclose the personally identifiable information gathered in the census under penalty of law. Census Bureau employees are required to swear an oath of confidentiality, and anyone outside of the Census Bureau cannot see individual census responses.

Finally, and most importantly, no data collected by the Census Bureau may be used without the consent of the individual as evidence or for any enforcement action, lawsuit, or judicial or administrative proceeding.18

(Find more information on census confidentiality and protection from malicious data use at the hyperlinks. See this report from the Brennan Center for Justice, which further explains census confidentiality.)

What protections exist for data sharing among the agencies listed in Trump’s executive order?

The Census Bureau regularly enters agreements with other agencies and departments to receive administrative records. In compliance with Title 13 of the U.S. Code, the bureau strips personally identifiable information from the records it gets from other departments and is legally prohibited from sending those records back to the Department of Homeland Security (including U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement).

Section 552(a) of the Privacy Act allows individuals’ data to be shared with the Census Bureau for statistical purposes, but other agencies may not share these records with each other without the written consent of the person who is the subject of the record. The only use outside of this restriction is transmission of the data between administrative agencies (not the Census Bureau) for law enforcement, but 22 even this use requires that the head of an agency make a written request to the agency whose records it wants to access. The head of the agency must also specify exactly the portion of the record they want and the law enforcement activity for which it will be used.

TAKEAWAY: Multiple legal protections are in place to prevent census citizenship data from being used for immigration or law enforcement. The data is intended for redistricting and influencing policy and laws.

Census Bureau on Data Sharing

Terms

Administrative Data (Administrative Records): Any records that agencies collect and maintain to administer the programs that they run.

American Community Survey (ACS): An annual survey sent to a random sample of households in the United States to learn about the characteristics of American communities. Respondents are asked questions about their income, citizenship, race and ethnicity, etc.

Apportionment: The distribution of the 435 U.S. House of Representatives districts among the states based on each state’s total population. Apportionment takes place after each de- cennial census.

Citizen voting age population (citizen voting eligible population): The number of people liv- ing in a specific area, such as a census block or congressional district, who are citizens aged 18 or older. That data is currently obtained from the American Community Survey (ACS). This is a special tabulation providing data on citizen voting age population by race and ethnicity.

Citizen voting age population (CVAP) redistricting: An effort to let states erase non-citizens and minors from representation in legislative and Congressional maps by deliberately omitting them from the count used to draw districts. Also referred to as citizen voting eligible population.

Coverage (under-coverage, over-coverage): This refers to how much of the population is overrepresented or underrepresented in a set of data.

Decennial Census: A count of all people living within the United States that the Constitution requires the federal government to conduct at the start of each decade (every 10 years).

Microdata: Data on specific individuals.

Person-Address Pairs: The combination of a unique person with an address. These are used to link administrative records to census respondents.

Public Law 94-171: Provides small-area population tabulations to each of the 50 state leg- islatures and to their governors in a nonpartisan manner. This is provided no more than one year after the decennial census.

Redistricting: The configuration and reconfiguration of the geographic boundaries of voting districts to determine representation in a governmental body (e.g., Congress, state legislatures, city councils, school boards, county commissions). During redistricting, lines are redrawn to determine the geographical boundaries for districts that elected officials will represent.

Sampling: The process of or method for obtaining information from a randomly selected and smaller subset of a larger population to infer information about the larger population. Sam- pling and statistical inference are used in circumstances in which it is impractical to obtain information from every member of the population.

Tabulation: The process of placing classified data into tabular (summary) form.

Endnotes

- Census Bur Redistricting File (Public Law 94-171) Dataset. February 03, 2011. https://www.census. gov/data/datasets/2010/dec/redistricting-file-pl-94-171.html

- Defined by the Statistical Programs and Standards office of the S. Office of Management and Budget in Directive 15 (issued in 1977 and revised in 1997). Originally, race tabulation groups included “white,” “black,” “American Indian/Alaska Native,” “Asian/Pacific Islander,” and “some other race.”

- Requested by the state legislatures and Department of Justice for the 1990 Census Redistricting Data

- Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 [1986]. https://suprjustia.com/cases/federal/us/478/30.

- Groen, 2012. “Sources of Error in Survey and Administrative Data: The Importance of Reporting Procedures.” Journal of Official Statistics 28 (2): 173–98.

- Coutin, Susan 2003. Legalizing Moves: Salvadoran Immigrants’ Struggle for U.S. Residency. University of Michigan Press.

- Hagan, Jacqueline 1994. Deciding to Be Legal: A Maya Community in Houston. Temple University Press.

- Census Bur American Community Survey. Coverage Rates and Definitions. July 12, 2018. https://www. census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/methodology/sample-size-and-data-quality/coverage-rates-definitions. html.

- Van Hook, Jennifer, and James 2013. “Citizenship Reporting in the American Community Survey.” Demographic Research29 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.1.

- De La Puente, 2004. “Census 2000 Ethnographic Studies.” U.S. Census Bureau, p. 15. https:// www.census.gov/pred/www/rpts/Ethnographic%20Studies%20Final%20Report.pdf.

- De La Puente, 1995. “Using Ethnography to Explain Why People Are Missed or Erroneously Included by the Census: Evidence from Small Area Ethnographic Studies.” U.S. Census Bureau.

- Nichols, Vanessa Cruz, Alana W. LeBrón, and Francisco I. Pedraza. 2018. “Policing Us Sick: The Health of Latinos in an Era of Heightened Deportations and Racialized Policing.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (2): 293–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517002384.

- Pedraza, Francisco , and Maricruz Ariana Osorio. 2017. “Courted and Deported: The Salience of Immigration Issues and Avoidance of Police, Health Care, and Education Services among Latinos.” Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies 42 (2): 249–66.

- Asian Americans Advancing Factsheet on the Census, Confidentiality and Japanese American Incarceration. https://censuscounts.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/AAJC-LCCR-Census-Confidentiality- Factsheet-FINAL-4.26.2018.pdf

- The forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War

- Dwork, 2011. “Differential Privacy.” In Encyclopedia of Cryptography and Security, edited by Henk C. A. van Tilborg and Sushil Jajodia, 338–40. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419- 5906-5_752.

- U.S. Census Bur 2018. “Handbook for Administrative Data Projects.” https://www2.census.gov/foia/ ds_policies/ds001_appendices.pdf.

- U.S. Title 13. Section 9. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2007-title13/pdf/USCODE- 2007-title13.pdf.

Related Resources

Report

Unlocking Fair Maps: The Keys to Independent Redistricting

Report

The Roadmap for Fair Maps in 2030

Report